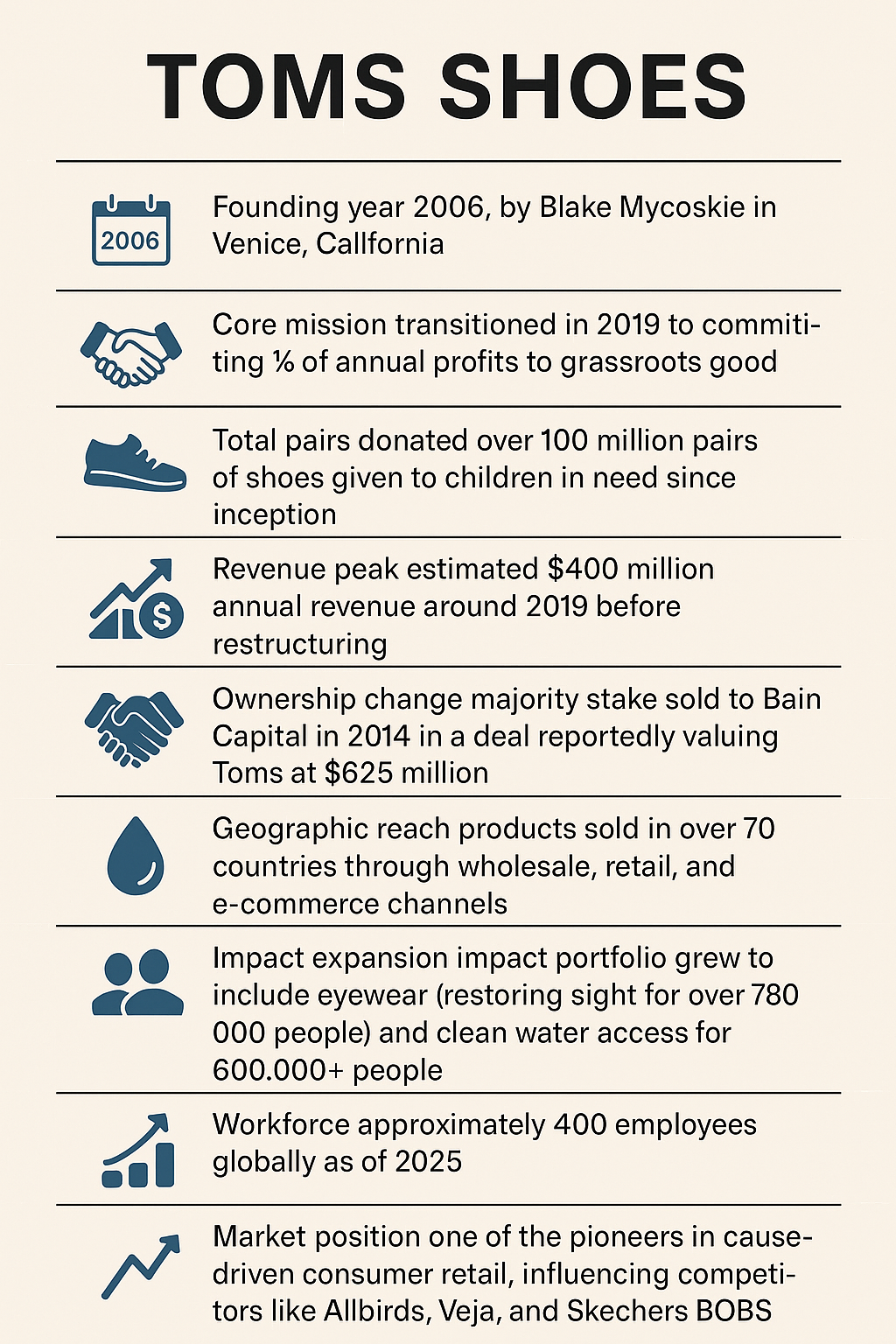

Toms Shoes, founded in 2006 and headquartered in Los Angeles, California, is a for-profit social enterprise known for its pioneering One-for-One mission – donating one product for each product sold.

The company’s core offerings include casual footwear (notably the alpargata canvas slip-on), as well as eyewear, coffee, and apparel, all tied to charitable causes.

Toms experienced rapid early growth and global recognition by marrying commerce with philanthropy: within its first year it sold 10,000 pairs of shoes and gave away 10,000 pairs to children in need.

Over the next decade, Toms scaled into a $300–400 million business with products sold in 500+ retail locations worldwide.

By 2019, the company had donated nearly 95 million pairs of shoes in 70 countries.

However, Toms’ journey also illustrates the challenges of sustaining momentum in a competitive, evolving market.

After its initial success, growth plateaued and debt mounted, culminating in a 2019 debt restructuring in which creditors took control of the company and founder Blake Mycoskie relinquished ownership.

In response, Toms pivoted its giving strategy – moving from a strict one-for-one donation model to pledging one-third of profits to a charitable fund addressing a broader range of issues.

New management refocused the brand on product innovation (e.g. sneaker-style footwear) and on younger consumers (Gen Z), aiming to rejuvenate sales and relevance.

Its story offers key lessons in balancing purpose with profit, adapting to consumer trends, and the importance of responsible financing.

The following case study provides an in-depth look at Toms’ history, industry context, competition, business model, financial performance, marketing, operations, challenges, and future outlook, with a data-driven and objective lens.

Company Background & History

Toms was founded in 2006 by entrepreneur Blake Mycoskie, following a formative trip to Argentina. There, Mycoskie encountered children without shoes and was inspired to create a business solution to this social problem.

The concept – originally dubbed Shoes for Tomorrow Project – was to develop a modern version of the Argentine alpargata shoe for the U.S. market, and for each pair sold, donate one pair to a child in need.

Mycoskie sold his small tech company and raised $500,000 to launch Toms Shoes (the name “TOMS” derived from “Tomorrow”).

In May 2006, he produced an initial batch of 250 pairs and started selling them in Los Angeles. A Los Angeles Times article spotlighting Toms’ mission spurred immediate demand – orders surged to nine times the available stock – and Toms sold 10,000 pairs in its first year, leading to 10,000 donated shoes distributed to Argentine children by the end of 2006.

This ingrained the One-for-One model as the DNA of the company from day one.

The goal was not just charitable giving, but building a self-sustaining social enterprise where charitable impact scales with commercial growth.

Early on, Toms even established a non-profit arm (“Friends of Toms”) to involve volunteers in its giving trips, signaling how integral the mission was to its operations.

This approach earned Toms recognition as a trailblazer in social entrepreneurship.

Key Milestones

Over the years, Toms has hit numerous milestones that mark its evolution:

- 2006: Company founded in Venice, CA; first 10k pairs sold and donated in Argentina.

- 2007: Launches annual “One Day Without Shoes” campaign to raise awareness of children’s health and education issues related to shoelessness. That year Toms also won the People’s Design Award from the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, reflecting its blend of good design and good deeds.

- 2011: Achieves distribution in over 500 retail outlets worldwide and expands into Toms Eyewear, applying the one-for-one model to eyesight (each purchase helps fund vision care). This marks Toms’ first product line extension beyond shoes.

- 2012: Surpasses 2 million pairs of shoes given away in over 40 countries. Toms gains academic recognition as a case study in business ethics and social enterprise.

- 2014: Introduces Toms Roasting Co. (coffee), where each bag sold funds a week of clean water for a person in need. Also launches a Toms Bags collection in 2015, funding safe birth services for mothers with each bag purchased. These moves signal a broader application of the one-for-one concept to new categories and causes.

- 2014 (August): Bain Capital acquires 50% of Toms in a deal valuing the company at $625 million. Mycoskie sells this stake to fund other social ventures (he personally netted ~$300 million) and retains the other 50% and his title of “Chief Shoe Giver”. The Bain partnership is aimed at fueling faster global growth while upholding Toms’ mission, with Bain even matching funds to support social entrepreneurship ventures initiated by Mycoskie.

- Leadership Changes: Following the Bain deal, Mycoskie transitioned from day-to-day leader to more of a brand figurehead. Professional management was brought in: Bain installed Jim Alling (former T-Mobile COO) as CEO to strengthen operations and supply chain. This was a pivotal shift from founder-led growth to PE-backed management.

- 2016–2018: Toms faces slowing growth and rising debt from the leveraged buyout. Credit ratings agencies (S&P, Moody’s) downgrade Toms’ debt as the company struggles to reignite sales and maintain profitability under the burden of a $300 million loan used to finance Bain’s buyout. During this period, Mycoskie remained public-facing (for example, in 2018 he led a major Toms campaign against gun violence, donating $5 million to the cause) but did not run daily operations.

- 2019 (Dec): Confronting continued sales declines and unable to service its debt, Toms undergoes a debt-for-equity restructuring. A group of creditors led by Jefferies Financial, Nexus Capital, and Brookfield Asset Management assume ownership control, effectively ousting Bain and Mycoskie as owners. The creditors inject $35 million in new capital to stabilize the business and reaffirm commitment to Toms’ giving ethos. Mycoskie departs with no equity, marking the end of an era.

- 2020: Magnus Wedhammar (a former Nike/Converse executive) is appointed CEO in early 2020 to lead Toms’ turnaround after the takeover. Under Wedhammar, Toms announces it will retire the One-for-One model in favor of a new impact strategy (pledging at least 1/3 of profits to grassroots good) to better resonate with modern consumers.

- 2020–2021: Toms, like most retailers, is hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. U.S. footwear sales dropped ~15% in 2020 industry-wide, and Toms’ largely wholesale business saw major declines. The company doubled down on e-commerce (which fortunately became more than half of its sales by 2020) and had its best online revenue year ever despite overall revenue falling (more details in Financial Performance). Toms also redirected giving to pandemic relief, donating over $2 million to COVID-19 efforts in 2020 as part of its new giving fund approach.

- 2022–2025: With a restructured balance sheet and refreshed strategy, Toms has been attempting a brand revival. It has expanded product offerings (more sneaker-like shoes) and shifted marketing to target Gen Z consumers and their causes (e.g. funding initiatives for mental health, ending gun violence). As of 2023, Toms remains a private company controlled by its creditor-owners, and has slimmed down (approx. 285 employees in 2023, vs. 500 in 2019) to operate more efficiently.

Evolution of Ownership & Structure

In summary, Toms’ ownership journey went from founder-owned, to half-owned by private equity (2014–2019), to fully owned by financial investors post-2019. Leadership correspondingly shifted from Blake Mycoskie’s charismatic founder-led style to professional managers (Alling, Wedhammar) with turnaround expertise.

The business model saw pivots from a single-product focus to multi-category offerings, and eventually a pivot in the giving model itself (from literal one-to-one donations toward a more flexible profit allocation for impact).

Throughout these changes, Toms’ core mission of using business to improve lives remained, though how it executes that mission has adapted to feedback and circumstances.

Industry & Market Analysis

Toms Shoes operates in the global footwear and apparel industry, with a focus on the casual footwear segment and an emphasis on socially conscious consumer goods.

The global footwear market is large and growing: valued at roughly $460 billion in 2024, it is projected to reach about $790 billion by 2032.

Annual growth in the sector has typically been in the mid-single digits, driven by rising incomes, fashion cycles, and increasing demand in emerging markets.

In the past 5–10 years, major trends have included the rise of athleisure (consumers shifting to athletic-inspired and comfort footwear), the growth of direct-to-consumer (D2C) brands, and a surge in sustainability and conscious consumerism.

Within the footwear space, casual shoes (Toms’ primary category) hold the largest market share globally, thanks to their comfort and versatility.

However, a notable trend has been the “sneakerization” of consumer preferences – even outside of sports, sneaker-style shoes have gained popularity at the expense of simpler casual flats.

This trend became especially pronounced in the late 2010s and was accelerated by lifestyle changes during COVID-19 (remote work, increased focus on comfort).

Another key industry factor is the retail channel transformation. Over the last decade, footwear sales have increasingly moved online, and brands that built strong D2C e-commerce or controlled retail have outperformed those dependent on third-party stores.

Toms historically sold through hundreds of boutique and department store accounts globally, but by 2020 it had developed its own robust e-commerce.

This shift insulated it somewhat during the pandemic, when brick-and-mortar retail contracted ~15% in the US in 2020. The broader trend suggests that omnichannel capability (a mix of online, own stores, and wholesale) is crucial in the footwear market.

Market Segments & Target Customers

Toms’ target market has evolved. Initially, its prototypical customer was the socially conscious millennial – often female, college-aged or young adult, interested in fashion but also keen to support causes.

Indeed, Toms became something of a movement on campuses, with over 280 Toms campus clubs formed by 2014 to advocate the brand’s mission.

These consumers were drawn by Toms’ story and value proposition of “purchase with a purpose.”

Surveys consistently show broad support for cause-linked brands – for example, 91% of consumers say they are more likely to buy from companies that support social or environmental issues – a sentiment that Toms successfully tapped into.

The company also garnered celebrity fans (from fashion influencers to Hollywood stars) which helped broaden its appeal beyond just the college demographic.

Over time, as millennials aged and the market became saturated with similar products, Toms has refocused on a new generation: Gen Z (teens and early 20s).

This cohort also cares about social causes but engages differently – expecting brands to be authentic, issue-driven, and trendy.

Toms’ recent strategic refresh explicitly targets Gen Z interests, aligning giving to causes like mental health and ending gun violence, and featuring young activists in marketing campaigns.

Geographically, Toms’ strongest market has been the United States, which is the largest footwear market globally and where the brand’s story initially resonated.

The company has also had a presence in Europe, Canada, and select Asian markets through retail partnerships and its website.

The Asia-Pacific region is the fastest-growing footwear market (over 32% global share by 2024). Toms has room to expand there, although its socially-driven messaging may need localization.

Key Demand Drivers

Several factors drive demand in Toms’ market segment:

- Conscious Consumerism: Modern consumers increasingly factor social impact into purchase decisions. In one study, 94% of global consumers said, price and quality being equal, they would switch to a brand that supports a good cause.

Its growth coincided with an era (late 2000s–2010s) of rising interest in corporate social responsibility. This demand driver remains relevant – if anything, Gen Z expects even more from brands in terms of social justice and sustainability.

However, because cause marketing is now more common (many brands boast charitable tie-ins), Toms no longer has that space to itself, potentially diluting the impact unless it differentiates its cause strategy.

- Fashion and Comfort Trends: The popularity of Toms’ signature product was partly due to a fashion trend favoring simple, vintage-inspired looks (the canvas espadrille) in the late 2000s.

As styles shifted to athletic leisure, demand for Toms’ core shoe waned. Conversely, new product launches (boots, sneakers) can tap into fresh demand. Overall footwear demand is also influenced by seasons and cultural norms (e.g. casual shoes vs. formal).

Toms, by focusing on casual, benefited from a casualization trend in workplaces and everyday wear. - Economic and Health Factors: During economic expansions, consumers are more willing to spend on discretionary fashion items and also on premium products that “give back.”

In downturns or uncertain times, spending contracts. For instance, the pandemic saw a sharp decline in overall footwear purchases as people stayed home.

However, Toms’ mid-range pricing (~$50-$70 for shoes) and charitable aspect may provide some resilience – consumers might justify a purchase knowing it helps someone else.

Additionally, health crises can influence product demand (closed-toe shoes in public health campaigns, etc., though not a primary factor for Toms’ fashion-oriented sales). - Regulatory/Policy Environment: While not a major direct driver for Toms’ demand, certain policies can have indirect effects.

For example, tariffs on imported footwear (US-China trade policies) can raise prices, affecting demand. Also, any regulations on cause marketing or B Corp certifications can shape consumer trust.

By being a certified B Corporation, Toms commits to higher standards of social and environmental performance, which can attract customers and investors seeking verified ethical companies. - Technological Innovations: In footwear, tech includes both product tech (new materials, 3D knitting, etc.) and marketing tech (social media, e-commerce platforms).

Toms has not been a tech-driven product innovator (it makes fairly simple shoes), but it has leveraged technology in marketing.

Early adoption of social media campaigns (the One Day Without Shoes campaign spread via Facebook/YouTube) and e-commerce were critical to building demand without huge ad budgets.

Today, digital marketing trends (influencer partnerships, TikTok, etc.) are key – Toms’ ability to engage on these platforms will drive future demand among younger consumers.

Market Size & Growth Projections

In Toms’ niche of casual footwear and ethical fashion, growth is moderate but steady. The overall footwear sector is growing ~4–5% annually in the mid-2020s. Segments like athletic footwear are growing slightly faster (projected ~4–7% CAGR globally), while traditional casual footwear grows a bit slower, though still positive.

The “ethical fashion” market (which includes brands emphasizing social or environmental causes) has been growing as conscious consumerism goes mainstream.

Toms’ pivot to incorporate sustainability (using recycled materials in some shoes) aligns with a key growth area: one industry report notes sustainable footwear is in high demand and major brands are expanding eco-friendly lines to meet it.

In terms of dollar figures, North America (especially the U.S.) remains the largest market for Toms-like products, but slower growing.

Asia-Pacific is the fastest-growing region for footwear demand (due to rising middle classes in China, India, etc.). If Toms can localize its model, these markets represent significant growth potential.

Overall, the industry context for Toms is one of opportunity coupled with intense competition. Demand for comfortable, stylish shoes is stable and rising globally, and demand for socially responsible brands is high.

The challenge lies in differentiating in a crowded space and keeping pace with changing consumer tastes. Toms’ experience has shown that capturing an early trend (cause marketing) can catapult a company, but sustaining that advantage requires continual adaptation in a dynamic market.

Causeartist BackOffice

Your Mission-Aligned Operations Team

From investor-ready financials to growth strategy, HR, compliance, and custom software—Causeartist BackOffice is your all-in-one operational partner. Built for impact startups, funds, and nonprofits, and powered by our experts.

Let us handle the back office—so you can stay focused on impacting the world.

Competitive Landscape

Toms carved out a unique position with its one-for-one model, but it faces competition from both traditional footwear companies and mission-driven upstarts. Its top competitors can be grouped into a few categories:

Established Footwear Brands (with similar products): Major casual footwear players like Skechers and Vans have overlapped with Toms’ product domain. Notably, Skechers launched a line called BOBS in 2010 that mimicked Toms’ canvas slip-ons and one-for-one donation concept (Skechers pledged to donate shoes to children for each BOBS shoe sold).

This direct copycat move by a large company was a competitive response to Toms’ success. With Skechers’ extensive distribution and lower price points, BOBS shoes quickly flooded the market, potentially siphoning off Toms’ budget-conscious customers.

Likewise, brands such as Converse (with its casual Chuck Taylor sneakers) or Keds offer alternatives in the casual canvas category, though without the philanthropic component.

These incumbents have strong brand recognition and retail presence, often competing on style and price. Toms struggled when competitors undercut prices – one reason its sales slowed was that rivals produced similar styles more cheaply as the novelty of Toms’ model wore off for consumers.

2. Socially-Conscious Newcomers: Toms’ one-for-one idea inspired a wave of mission-driven brands. A prominent example is Warby Parker (eyewear), which in 2010 adopted buy-one-give-one for glasses.

In footwear specifically, Allbirds (founded 2016) is a notable emerging competitor. Allbirds doesn’t do one-for-one, but it targets the ethical consumer with a focus on sustainability (natural materials like merino wool, carbon-neutral operations).

Allbirds’ casual sneaker is a substitute for a Toms shoe in a consumer’s wardrobe, especially for those who prioritize eco-friendliness over direct charitable donation.

Similarly, Rothy’s (launched 2016) makes women’s flats from recycled plastic and has gained popularity among conscious consumers.

These startups compete on a story (sustainability, fair trade, etc.) much like Toms competed on its giving story. They often start D2C (as Toms largely did) and use social media heavy marketing.

While Toms was a first mover in cause-branding, the field is now crowded with brands claiming various social or eco credentials, which challenges Toms to maintain leadership in the social good space.

3. Athletic Footwear Giants: Indirectly, companies like Nike, Adidas, and Puma are competition in the sense that they capture a large share of footwear spending, especially with the casualization trend.

Toms has acknowledged it’s not equipped to go head-to-head with performance sneaker makers. However, as consumers pivoted to wearing sneakers everywhere, Toms’ share of closet space was threatened.

Even these giants have been incorporating social responsibility (e.g., Nike’s community programs, sustainable materials lines) – not one-for-one, but they chip away at the differentiation Toms had.

Comparative Business Models & Strategies

- Toms: Sells mainly casual lifestyle products. Original model: for each product sold, donate an equivalent product or service. Revenue comes from one-time sales (no subscription or recurring service), through its website and wholesale partners. Pricing is mid-range (e.g. ~$50 for classic canvas shoes).

- Skechers (BOBS): A global footwear company with diverse lines and massive scale (multi-billion dollar revenue). BOBS by Skechers copied Toms’ product design (nearly identical-looking espadrilles) and cause appeal. However, Skechers’ business model is more traditional – it uses significant advertising, celebrity endorsements, and leverages a vast retail network.

The giving component, while marketed, is a smaller part of Skechers’ overall business (and Skechers is not a certified B Corp or similar). Pricing for BOBS shoes undercut Toms (often $30-$40 a pair), appealing to cost-conscious consumers who still liked the idea of giving shoes to kids. In essence, Skechers used its cost advantage and distribution might to commoditize the one-for-one shoe concept. - Allbirds: A venture-funded startup turned public company (IPO in 2021) that focuses on sustainability and comfort. Its business model is primarily D2C (online and branded stores). Product: casual sneakers and runners made from wool, eucalyptus fiber, etc. Pricing: around $95 for core styles (higher than Toms).

Allbirds emphasizes carbon footprint labeling and a mantra of “better for you and the planet,” appealing to environmentally conscious consumers. Unlike Toms, Allbirds does not donate one-for-one, but it invests in carbon offsets and renewable materials. Its marketing is heavy on digital and word-of-mouth (much as Toms was). In terms of go-to-market, Allbirds began online-only, then expanded to flagship stores in key cities. - Other Cause-Driven Brands: Warby Parker (eyewear) operates similarly to Toms but in glasses – D2C, one-for-one donations of glasses, and has grown significantly with an IPO in 2021.

Bombas (socks) uses a donate-a-pair model and is now a large private company. These examples underscore that Toms’ model proved replicable across industries.

While not direct competitors in shoes, they compete for the same “share of heart” of consumers looking to support good causes. If a consumer has limited discretionary spend for feel-good purchases, Toms must compete with these other mission-led products.

Competitive Advantages & Disadvantages of Toms:

Advantages:

- Brand Mission & Goodwill: Toms is virtually synonymous with one-for-one philanthropy – it built tremendous brand equity and goodwill as a pioneer of purposeful branding. This reputation can still differentiate Toms in a cluttered market, as many consumers remember Toms as “the original” compassionate commerce brand. The company’s B Corp certification further bolsters trust.

- First-Mover Customer Base: Having been around since 2006, Toms has an installed base of customers (millions have purchased its products) and followers on social media. There is residual loyalty among those who grew up with the brand, which newer entrants lack.

- Cause Integration Expertise: After years of giving, Toms developed deep partnerships with charities and NGOs in the field, distributing in over 70 countries and learning how to implement aid without as many missteps.

Competitors imitating the model had to catch up or sometimes faced skepticism about their commitment. Toms also preemptively addressed criticisms by altering its giving practices (e.g., producing 40% of donation shoes locally to support local jobs), showing agility in its CSR strategy. - Omnichannel Distribution: Unlike many new D2C startups, Toms is omnichannel – it sells via its website, its own stores, and hundreds of retail partners (Nordstrom, Whole Foods, Neiman Marcus, etc.). This broad availability helped Toms scale quickly and can be an asset as consumers still appreciate in-store shopping for shoes.

- Product Simplicity and Margin: The simplicity of Toms’ core shoe design meant it could be produced very cheaply at scale. This allowed Toms healthy gross margins even after donating a pair. While style fashion risk is a downside, simplicity also means easier manufacturing and inventory management compared to tech-heavy footwear.

Disadvantages:

- Lack of Diversified Product Portfolio: For a long time, over 50% of Toms’ revenue came from one style – the Classic Alpargata slip-on. This concentration made Toms vulnerable when that style fell out of favor. Competitors with broader catalogs (e.g., Skechers with athletic, casual, kids’, etc., or Nike with hundreds of models) are less exposed to a single-product risk. Toms’ attempts to expand (boots, sneakers, sandals) met mixed success and came relatively late.

- Easily Imitable Model: There was little proprietary about canvas espadrilles or the idea of donating shoes. Thus, as noted, competitors large and small cloned the idea. Toms trademarked the phrase “One for One”, but it couldn’t stop others from doing similar donation programs. With low barriers to entry, many charities and companies started shoe donation drives, eroding the uniqueness of Toms.

- Mission Fatigue and Criticism: Toms faced criticism from development experts that donating shoes doesn’t solve underlying poverty and could even harm local economies. This narrative, coupled with the notion that Toms made consumers “feel like benefactors” more than actually fix problems, may have dampened some enthusiasm over time.

While Toms did respond (adjusting manufacturing locations and eventually shifting to impact grants), the initial criticism highlighted that its model had a public relations vulnerability. Competitors not tied to a one-for-one promise (like Allbirds) don’t face the exact same critique. - Financial Constraints: The very act of donating a free product for each sold is effectively a cost on every sale. In boom times it’s manageable, but in lean times it squeezed margins. Once growth slowed, Toms’ high debt and philanthropic cost structure became a burden; it ended up with a Caa3 credit rating (distressed) by Moody’s during the worst of its slump.

In contrast, many competitors were better capitalized or didn’t carry the same cost obligations per sale. This made Toms less agile in responding with pricing promotions or heavy R&D investment, for example. - Brand Perception Challenges: Toms’ very strength – being known for its charitable model – had a flipside: some consumers saw Toms more as a charity than a cool brand. Among fashion-conscious customers, Toms shoes were not considered high style after the initial fad.

The brand has to work to reinvent its image to remain relevant (hence the new marketing with updated styling, etc.). Competing fashion brands that stayed on-trend (like Vans with new collabs, or Nike with celebrity partnerships) maintained stronger fashion credibility.

SWOT Analysis of Toms:

- Strengths: Powerful brand story and pioneer status in social entrepreneurship; a proven track record of impact (95M pairs donated by 2019) that resonates with values-driven consumers; strong distribution network and global reach (sold in 500+ stores internationally); high product margins on core items; loyal community of supporters and campus ambassadors built over years; agile marketing that leverages storytelling and experiential campaigns (e.g., One Day Without Shoes, giving trips).

- Weaknesses: Declining revenue in recent years (sales fell from nearly $300M in 2019 to $200M in 2020); overdependence on a once-trendy product without sufficient innovation (half of sales from the alpargata style); past financial instability due to debt and high cost structure (loan default risk in 2019); loss of founder in leadership, and limited presence in athletic or other high-growth footwear segments.

Additionally, Toms’ one-for-one model no longer differentiates it as much – it had to abandon that signature strategy to pursue a new approach in 2020, essentially giving up a branding element that made it famous. - Opportunities: Product line expansion and innovation, geographic expansion in emerging markets where brand awareness can be built (Toms could enter markets in Asia or Latin America not just as a giver but a seller, especially as those regions’ consumers become more brand- and cause-conscious); deepening the direct-to-consumer channel (growing its e-commerce, since that proved successful during the pandemic, and possibly opening pop-up stores or partnerships for younger demographics); forging collaborations with designers or celebrities to refresh its fashion image (for instance, limited edition collections that can create buzz); and capitalizing on its impact grant model to support timely causes (which can generate positive PR and connect with younger consumers on issues they care about, such as racial justice or climate action beyond shoe donations).

Another opportunity is to leverage technology – for example, using digital customization (allowing customers to design their own Toms), or enhancing their impact tracking so customers see the direct effect of their purchase, which could drive higher engagement and repeat sales. - Threats: Competition remains a big threat – not only from lookalikes and large brands as discussed, but also the general saturation of the casual footwear market. Style trends could further move away from Toms’ identity (if, say, chunky sneakers or tech-enabled footwear dominate, Toms’ minimalist canvas shoes might seem too basic).

Economic downturns or inflation can threaten sales; Toms’ customers might opt for cheaper alternatives or delay shoe purchases when budgets are tight (and cheap knock-offs or second-hand markets can undercut them).

Additionally, cause marketing fatigue or skepticism is a threat – consumers have grown warier of “performative” corporate social responsibility. If Toms is perceived as not delivering real impact, it could face backlash, especially given new studies that showed some negative externalities of shoe donations.

Finally, as a private company with new owners, there’s execution risk: any internal strategic misstep or inability to connect with Gen Z could result in Toms further losing relevance while nimbler start-ups take its place.

Business Model & Revenue Streams

Core Business Model

Toms Shoes generates revenue by designing, manufacturing (via third parties), and selling footwear and other lifestyle products to consumers. The primary revenue stream is the sale of shoes – casual canvas flats, as well as boots, sneakers, and sandals.

Over the years Toms also added sunglasses, coffee beans, apparel, and accessories (bags) as product lines, each tied to a cause (e.g., eyewear sales help fund eye care, coffee sales fund clean water). These extensions, however, contribute a smaller share of revenue compared to footwear. Essentially, Toms is a product retail business with a built-in charitable cost for each sale.

Toms’ original one-for-one model meant that for every product sold, it incurred the cost of giving an item away (plus logistics of distribution). In practice, Toms treated these give-aways as part of its marketing and customer acquisition cost – a way to create a compelling proposition that would attract buyers without traditional advertising. Indeed, the company relied on the model to generate word-of-mouth rather than spending heavily on ads.

This strategy saved marketing dollars but shifted costs into COGS (cost of goods sold) due to the donation.

Revenue by Segment

Toms does not publicly break out detailed segment financials (as a private firm), but some patterns are known:

- By product category: Footwear is by far the largest segment. Within footwear, the classic women’s and unisex alpargata slip-ons were historically the volume driver (multiple millions of pairs per year at the peak). Other shoe styles (boots, sneakers) have grown in mix since 2019 as Toms intentionally diversifies its catalog.

Eyewear and coffee remain niche – for example, the coffee line was sold mainly online and in a few Toms café-stores; it’s more of a brand extension than a major revenue source.

Similarly, Toms’ apparel and bag offerings (launched mid-2010s) were limited in assortment. We can infer that shoes likely account for over 80% of revenue in recent years, with eyewear perhaps ~10% and other items the remainder. - By geography: The United States has contributed the majority of Toms’ sales (likely 60-70% at times), given the brand’s origin and strongest awareness here. International markets in Europe (UK, France, etc.), and some in Asia and Latin America, were served via retailers and regional websites.

Toms’ giving efforts have a wider global footprint than its sales footprint (it gives in many developing countries where it doesn’t sell much, or sells to aid workers/expats at best).

Toms opened a flagship store in London in 2013 and has distribution in Canada, Australia, and Western Europe through retailers – those regions likely form a solid secondary revenue chunk. - By channel: Historically, wholesale to retailers was significant – by 2011, over 500 retailers carried Toms. This included department stores (Nordstrom, etc.), footwear chains, and small boutiques.

Over time, Toms invested in direct channels: its own e-commerce (toms.com) and a handful of company-owned stores. By 2020, direct-to-consumer channels accounted for over half of sales, a purposeful shift to improve margins and customer connection.

This helped Toms in the pandemic, as its online revenue hit a record high in 2020 despite overall sales falling. Toms’ business model now relies more on direct sales (higher margin per unit) and less on wholesale (higher volume but lower margin per unit), which is consistent with many brands’ strategies in the digital era.

Unit Economics

While granular unit economics (like exact customer acquisition cost or lifetime value) are proprietary, we can discuss qualitatively:

- Customer Acquisition & Marketing Efficiency: Early in its life, Toms enjoyed extremely efficient customer acquisition due to its viral story. Press articles, campus activism, and social media sharing meant Toms spent relatively little on traditional advertising.

For example, an AT&T commercial in 2010 featured Toms’ story, giving massive exposure essentially for free. The concept itself (“buy one give one”) served as marketing. As a result, one could say Toms’ effective CAC was low in the early years – many customers were acquired via word-of-mouth.

In later years, with more competition, Toms had to do more conventional marketing (paid ads, influencer campaigns). Still, the built-in philanthropy can be seen as part of CAC: the company “pays” a pair of shoes to acquire a customer. If that cost is ~$5, it’s quite cost-effective compared to, say, a $20 Facebook ad click – and it directly builds goodwill. - Lifetime Value (LTV): Toms aims for repeat purchases by fostering loyalty to its mission. Many customers did buy multiple pairs over time, treating Toms as a go-to casual shoe or gifting Toms to others.

The product’s durability and fashion nature means it’s not consumable, so LTV depends on introducing new styles or the customer’s personal attachment. The presence of Toms in major retail also made one-off purchases common (someone might buy one pair out of curiosity or to support the cause, but not necessarily become a frequent shopper).

The introduction of new product lines (like sunglasses or boots) provided cross-selling opportunities to increase LTV per customer.

It’s worth noting that some of Toms’ best customers were likely those engaged in its community (like campus club members who would buy many pairs over time and evangelize the brand).

Concrete LTV figures aren’t public, but maintaining a strong customer community has been central to extending LTV through loyalty and brand connection. - Gross Margins: Toms’ gross margin on shoes has been high relative to many footwear brands. As mentioned, a $50 retail canvas shoe might cost under $10 to make and donate together. Even wholesale margins were decent since retailers keystone (double) the cost – so if Toms sold a pair to a retailer for $25 (who sells to consumer for $50), that $25 likely covers production of two pairs (~$7-$10) plus leaves $15 to contribute to overhead.

Gross margins likely exceeded 50% historically, which helped fund the philanthropic operations and any marketing.

Under Bain, Toms worked to streamline its supply chain, presumably to improve margins further or offset rising costs. One area to watch is if Toms moves into more complex products (sneakers with more materials and labor, for example), margins per unit could shrink compared to the simple slip-ons. - Contribution Margin & Profitability: While gross margins were strong, Toms did incur significant SG&A expenses: managing a global giving program (staff, logistics), opening flagship stores, and the general costs of running a global brand.

We know that by mid-2010s, Toms struggled to stay profitable – S&P in 2015 cited difficulty “returning to profitability”. This suggests that as growth slowed, overhead and interest on debt dragged it into losses.

Customer acquisition became more costly when growth plateaued, because the easy organic reach had saturated. So, Toms’ unit economics were great to a point, but scaling beyond the initial passionate audience required more spend (or new products) to attract customers, and the fixed costs (including interest on $300M debt) weighed heavily. - Recurring Revenue: Toms does not have a subscription or recurring fee model; it depends on continuous sales of new goods. However, one could see repeat purchases and new product launches as a form of recurring revenue from its loyal base.

Toms tried a coffee club (coffee could have been a subscription model) but there’s little evidence that became a significant recurring revenue stream.

The move to one-third of profits to charity instead of one-for-one might also improve effective margins on each sale (since in down years, they won’t give away more product than finances allow).

This change could make the business model more scalable and resilient – in profitable times they give more, in lean times the giving automatically scales down as it’s pegged to profits, not volume. Essentially, the new model turns the charity expense into a variable cost tied to profitability rather than a fixed cost per unit.

Revenue Growth and Trends

In its first 5-6 years, Toms experienced explosive growth – reportedly surpassing $300 million in revenue by around 2012, a stunning trajectory from zero in 2006. Growth was propelled by rapid adoption in the U.S. and then internationally, plus the viral nature of its brand.

After 2012, growth began to slow; by 2014, Mycoskie himself sought a partner (Bain) to “help it grow faster” beyond that point.

Under Bain, Toms did expand distribution and product lines, but growth did not meet expectations – by 2019 revenue was estimated at just under $300 million, indicating essentially flat or declining sales compared to the mid-2010s.

Then the pandemic caused a sharp drop (~30% decline from 2019 to 2020) with 2020 revenues slightly above $200 million.

Operations & Organizational Structure

Behind the scenes of the Toms brand is an operational framework that allowed the company to deliver both products and social impact across the globe. Key aspects include its footprint, supply chain, internal organization, and approach to managing operational challenges:

Operational Footprint & Supply Chain

- Manufacturing: Toms does not own factories; it outsources production of its shoes and other products to manufacturers, primarily in Asia (China, Vietnam, India) and also in some countries where it gives shoes.

In response to criticism about giving free imported shoes into poor countries, Toms moved about 40% of its shoe production for donation to countries where it donates (such as Kenya, Ethiopia, Haiti, and India).

This initiative, started in early 2010s, meant some of the shoes that Toms gives away are actually produced locally, creating jobs in those regions – a strategic operational decision aligning with its social mission.

For its retail products, Toms likely concentrates production in cost-effective locations with reliable quality. A story in 2013 indicated the cost to manufacture a pair was extremely low (under $5), implying use of countries with low labor costs. - Distribution Centers: Toms manages logistics for two flows: one for retail products to customers/retailers, and one for donated goods to charity partners. It probably uses third-party logistics (3PL) providers in key regions.

In the U.S., it would have a warehouse (possibly in California or a central location) to ship e-commerce orders and wholesale orders.

For the giving side, Toms coordinates with NGOs – often shipping large batches of shoes to the partner organizations’ warehouses in-country, which then handle distribution to communities.

Coordinating these giving trips can be complex: timing deliveries with volunteer schedules, getting through customs (importing a large donation requires paperwork, etc.), and ensuring the right shoe sizes and types for recipients (Toms often provides children’s canvas shoes, which are simpler to size).

Workforce & Offices

- Toms grew from a small Venice, CA apartment operation to an organization that had 500 employees around mid-2010s. The headquarters is in Los Angeles (Playa Vista area), which houses design, marketing, e-commerce, and corporate functions.

Toms also has had satellite offices for regional operations (for instance, an office in The Netherlands for Europe was reported, as well as perhaps an office in Hong Kong or similar for supply chain coordination). - After the 2019 restructuring, Toms downsized to about 285 employees by 2023. This suggests a leaner operation likely focusing on core teams. Many non-essential or duplicate roles (perhaps wholesale support staff, etc.) might have been cut to reduce costs.

Challenges & Crisis Management

Throughout its history, Toms has faced a number of significant challenges – some external, some self-inflicted – that tested the company’s resilience and values. Below we examine a few key setbacks and how the company responded:

1. Criticism of the One-for-One Model & Social Impact Effectiveness

By the early 2010s, as Toms’ profile grew, so did scrutiny of its charity model. Development experts and critics argued that giving free shoes could undermine local shoe sellers in poor countries and that it addressed a symptom (shoelessness) rather than root causes of poverty.

Some even suggested it fostered dependency or a “white savior” complex. These critiques posed a reputational crisis: the very selling point of Toms (doing good) was being questioned as potentially doing harm. Toms’ response was multi-pronged:

- Local Production: Toms acknowledged the concern and by 2013 committed to produce a significant portion of its giving shoes in the regions they’re distributed. As noted, 40% of donation shoes were made in countries like Ethiopia, Kenya, India, Haiti. This created local jobs and mitigated the argument that Toms was only dumping foreign goods.

- Partnership & Research: Toms engaged with academics and welcomed studies of its impact. A 2014 research paper did not find significant negative effect on local markets from Toms shoe donations (though with caveats). Later research highlighted potential psychological externalities, which Toms took into account. The company often stated that shoes were distributed in areas where local markets were minimal or where shoes served urgent health needs (e.g., rural areas prone to soil-transmitted diseases), to justify that their aid was well-targeted.

- Communication Shift: Toms slightly shifted its narrative from “we give shoes” to “we’re addressing needs like health and education (by providing shoes so kids can go to school, etc.)”. It framed the giving as a bridge to opportunity rather than a handout. Also, Toms was transparent about the critiques in some of its communications, striving to show it’s learning and adapting – a crucial aspect in crisis PR for a mission-driven brand.

- Ultimate Pivot (2019): Over time, Toms recognized one-for-one need not be literal to be impactful. In 2019, the company made the bold decision to decouple its giving from one-for-one and move to the “1/3 of profits to grassroots good” model. As Amy Smith said, this allowed addressing a broader range of pressing issues (e.g., gun violence, homelessness) beyond just shoe or eyewear donations. This was partly a response to the limitations and criticisms of one-for-one. By doing so, Toms essentially addressed the challenge by evolving the model – a strategic pivot to ensure its social impact remained positive, relevant, and not easily critiqued as superficial.

- Outcome: The criticism, while perhaps tarnishing Toms’ simplistic narrative, ultimately drove the company to improve and mature its approach to giving. In the long run, this likely preserved Toms’ credibility as a sincere impact-driven company. The pivot to impact grants has been presented as a positive, future-oriented change and seems to have been accepted by consumers and media as a logical step in Toms’ journey (indeed, “walking away from one-for-one” was reported as a sign that Toms is listening and adapting).

2. Financial Crisis and Near-Bankruptcy (2019)

Perhaps the most perilous challenge Toms faced was the financial crunch that culminated in late 2019. After taking on heavy debt in the Bain Capital deal, Toms saw stagnant sales and was unable to meet its loan obligations. By 2019, its credit rating was deep into junk (Caa3), and $300 million in loans was due for repayment in 2020 which the company could not repay.

This was an existential crisis: failure to resolve it would mean bankruptcy, layoffs, and possibly the end of Toms as an independent entity. Toms and its stakeholders responded through:

- Debt Restructuring Negotiations: Behind closed doors, Toms’ management and Bain engaged with the creditors to find a solution. This resulted in a deal announced Dec 2019 where creditors agreed to take over the company in exchange for debt relief.

Essentially, Toms underwent an out-of-court restructuring: ownership transferred to creditors (Jefferies, Nexus, Brookfield) and the debt was reduced to a sustainable level. - Leadership & Ownership Changes: Bain Capital and Blake Mycoskie gave up their equity stakes (Blake went from founder-owner to no ownership). It was uncertain if Mycoskie would have any role post-restructure; in practice he stepped away from management entirely. Bain’s exit was effectively at a loss – a humbling outcome.

The new owners quickly signaled commitment by pledging $35 million new investment into Toms. They also retained focus on the mission in communications (the CEO’s letter reaffirmed continuing the giving commitment) to avoid staff or customer panic that “Toms will lose its soul.” - Interim Management Stability: At the time of takeover, Jim Alling was CEO and he communicated the news to employees emphasizing a “renewed future”. Shortly after, Alling (who had been leading under Bain) transitioned out and the new owners brought in Magnus Wedhammar (Jan 2020) as CEO. They likely also injected new blood in the board and management ranks, e.g., hiring a new CMO etc., to drive the turnaround. The transition was managed to keep the business running – suppliers, employees, and partners needed confidence that Toms would honor commitments. The infusion of capital helped assure vendors that operations could continue.

- Restructuring Plan: With debt off the table, Toms could focus on right-sizing. They initiated cost-cutting – reducing headcount by ~40%, closing unprofitable stores (if any), and narrowing product focus to best-sellers. The giving model change in 2019 (discussed above) also dovetailed with this, as it reduced the pressure of fulfilling donations irrespective of profitability. Instead, giving would be scaled to profits, which creditors would have insisted on to protect the company’s financial health.

- Outcome: Toms avoided bankruptcy and liquidation, a big win in crisis management. However, it was effectively a “restart” under new ownership. Many employees likely felt uncertainty, but the clear backing by the new investors and retention of mission probably kept morale from collapsing. The long-term impact is that Toms survived to refocus and gradually recover. The founder’s departure was bittersweet but possibly necessary; Mycoskie himself expressed that he was ready for new projects (and he had other ventures to pursue with the fund he created).

3. External Crises: Focus on the Family Backlash (2011) & COVID-19 (2020):

- Reputation Incident (2011): In mid-2011, Blake Mycoskie spoke at an event by Focus on the Family, a conservative religious group known for anti-LGBTQ positions. When word got out, many Toms customers (often socially liberal young people) were upset, perceiving that Toms might support that organization’s values. This was a PR crisis where Toms risked alienating its progressive-leaning base. Mycoskie responded swiftly with an apology, stating he was not aware of Focus on the Family’s controversial stances, that it was a mistake, and affirming that Toms stands for equal human and civil rights for all.

This clear and humble response helped contain the fallout. Toms also made efforts thereafter to vet partners more carefully and leaned into inclusive messaging (for example, later marketing often showed diversity in models, and Toms collaborated with charities that support LGBTQ youth in some campaigns). - Global Pandemic (2020): The COVID-19 pandemic was an external crisis that hit the retail/fashion industry broadly. For Toms, it meant store closures, supply chain disruptions, and a dip in consumer spending on non-essentials like shoes. Specifically, in 2020, U.S. footwear sales fell 15% and Toms’ wholesale orders were severely reduced as retail partners had inventory glut. Toms tackled this in several ways:

- Accelerating E-commerce: With physical retail constrained, Toms pushed more inventory and effort to online sales. They enhanced their website experience and possibly offered promotions to drive traffic. This paid off as 2020 became Toms’ best year for e-commerce revenue ever. More than half of sales were through its own channels, which not only compensated partially for lost wholesale but also at better margins.

- Product Mix Adjustment: Recognizing that consumers in lockdown wanted comfort, Toms highlighted its slippers, house shoes, and core comfortable slip-ons (shoes one can wear at home). It also delayed new fashion-forward launches since demand for trendy wear was down. Instead, Toms repurposed marketing to emphasize comfort and community.

- Community Support (Goodwill Marketing): Toms allocated one-third of its profits in 2020 to a COVID-19 Global Giving Fund, which provided grants to frontline organizations (like those providing mental health support or handwashing stations in vulnerable communities).

They publicly announced donations of over $2 million to COVID relief by mid-2021. This not only helped those causes, but signaled to consumers that Toms, even in hardship, was living its values. It likely endeared the brand further to customers who saw it as a company with a heart in a time of crisis. - Cost Control & Flexibility: Toms would have negotiated with suppliers to reduce or delay production orders when stores cancelled orders, to avoid massive overstock. The company also likely used government relief programs to support payroll in the short term (many businesses did). The prior restructuring ironically positioned Toms better for COVID – it had fewer expenses and some new capital to buffer the shock.

- Outcome: Toms emerged from 2020 bruised but not broken. Sales were down, but the company stayed solvent (thanks to having restructured just in time in 2019). Also, the pivot to digital and alignment with what consumers cared about (health, essential needs) possibly helped Toms pick up new customers or keep loyalty. By late 2021, as vaccines rolled out, there were signs of a footwear market rebound, which Toms hoped to capture.

The crisis reinforced the importance of omnichannel readiness and having a mission that can flex to current events (Toms wasn’t stuck only donating shoes; it could donate to COVID causes due to its new giving model).

4. Internal Strategic Drift

Another “challenge” was more gradual – the risk of losing focus by diversifying too much. The mid-2010s saw Toms launching coffee, bags, etc. While noble, not all of these took off, and some critics felt Toms might be straying from what it’s good at (shoes) in the name of chasing more one-for-one ideas.

This strategic dilution can hurt a brand (too many disparate products can confuse consumers and strain resources). Recognizing this, under new leadership, Toms refocused on its core product (footwear) and core demographic (younger consumers needing casual shoes).

The coffee cafés and such, while still existing, are not the main growth area now. Essentially, Toms’ response to this creeping challenge was to recenter the brand, as evidenced by Wedhammar’s quote: “We have a great opportunity to sneakerize the Alpargata… We’re not going to make sneakers that compete with Nike, but we will adapt our product”.

This shows restraint and clarity – addressing the earlier lack of focus by doubling down on what makes Toms unique (the Alpargata and its story) and updating it rather than chasing entirely new categories.

Key Takeaways & Lessons Learned

Toms Shoes’ journey offers a wealth of insights for entrepreneurs, socially-minded businesses, and the retail industry at large. Here are major lessons and takeaways gleaned from its case:

1. Purpose as a Growth Engine (and Its Limits)

Toms demonstrated that integrating a social mission into a business model can create powerful brand differentiation and customer loyalty.

The company grew explosively by giving customers a way to feel they’re making an impact with each purchase.

This “caring capitalism” approach turned customers into evangelists and gave Toms a marketing advantage with minimal spend.

Many companies (Warby Parker, Bombas, etc.) emulated this after seeing Toms’ success.

Lesson: A strong purpose can be a significant competitive advantage, especially with younger consumers who often choose brands aligned with their values (91% of consumers are more likely to buy from companies supporting a cause).

However, Toms also learned that mission alone isn’t enough to sustain growth indefinitely – the novelty can wear off, and consumers will scrutinize the actual impact.

Therefore, companies must continuously validate and communicate the effectiveness of their social impact, not just rely on good intentions. Purpose should evolve as the company scales (as Toms did by revamping its giving model in 2019 to keep it relevant and effective).

2. Innovate or Stagnate – Adapting to Consumer Trends

A stark lesson from Toms is the risk of resting on one successful product. Toms rode the popularity of its classic alpargata for too long while the market moved towards athletic styles and new competitors emerged.

Over-reliance on one product (accounting for ~50% of revenue) made the company vulnerable.

Lesson: Even if you have a hit product, invest in R&D and market research to anticipate shifts in consumer preference. Brands must balance consistency (maintaining what customers love) with innovation (offering something new to meet evolving tastes).

In Toms’ case, earlier diversification into sneakers or comfort tech might have softened the sales decline. The company is now catching up by “sneakerizing” its line – a reminder that it’s never too late to innovate, but earlier is better.

Also, monitor the competitive landscape: when Skechers and others introduced copycat products at lower prices, it signaled the need for Toms to differentiate beyond just the one-for-one concept and invest in unique design, quality, or other features to maintain an edge.

3. Financial Discipline is Crucial – Mission Doesn’t Excuse Mismanagement

Toms’ near-collapse under debt highlights that no amount of idealism can compensate for unsustainable finances. The Bain Capital deal in 2014, while providing growth capital, saddled Toms with a $300M loan that proved ruinous when growth slowed.

Lesson: Be cautious with leverage and growth-at-all-costs mentality, especially in retail where trends can be fickle. Social enterprises in particular should avoid overextending, because a failure doesn’t just mean financial loss but also loss of impact for communities they serve.

Toms had to undergo painful restructuring – an outcome that might have been mitigated with more conservative financial planning or incremental growth strategies. Now, with a leaner structure and profit-focused giving model, Toms can rebuild more sustainably.

The broader takeaway for other businesses is to align your financing strategy with realistic projections, and not assume that a beloved brand is invincible to market downturns or competition.

This includes maintaining healthy margins (Toms managed to keep good gross margins, but rising costs and debt interest eroded net margins) and cutting back or pivoting quickly when early signs of trouble appear (credit downgrades in 2015 were a warning).

4. Authenticity and Accountability in Social Impact

Toms was a pioneer, but it wasn’t immune to criticism. When confronted with evidence that its shoe donations might have unintended negative consequences, it took steps to address those issues (local manufacturing, adjusting donation practices).

Lesson: For companies building their brand on social impact, being transparent, listening to stakeholders (including critics), and willing to change course is vital for long-term credibility. It’s not enough to initiate a feel-good program; one must continuously ask, “Are we actually helping in the best way possible?” and adapt accordingly.

This willingness to improve can turn potential PR crises into opportunities to deepen your impact. Toms’ decision to diversify its giving portfolio in 2019 is an example of such accountability – it admitted that One-for-One, while iconic, wasn’t the be-all end-all, and evolved to a model potentially more aligned with current social needs.

This honesty likely preserved trust among consumers and is a lesson that doing good is a journey of learning, not a static promise.

5. The Power of Storytelling and Community in Marketing

Toms essentially wrote the playbook on modern cause marketing. It showed that a compelling story (Blake’s trip to Argentina, the barefoot kids, the simple promise of a shoe given) can build a global brand with very little paid advertising.

Engaging the community through events like One Day Without Shoes and campus clubs turned customers into an army of ambassadors.

Lesson: Emotional connection and customer engagement can yield marketing outcomes that money can’t buy. In an age where consumers are bombarded with ads, a genuine narrative and a participatory cause can cut through the noise.

This is applicable beyond social enterprises – any brand can benefit from finding a purpose or story that rallies a community (be it around sustainability, innovation, or lifestyle).

However, Toms also shows that the story must evolve. For instance, the company is rewriting its narrative for Gen Z by focusing on issues like gun violence prevention and mental health, which are more resonant with today’s youth than perhaps shoe donations. Brands should regularly refresh their story to stay relevant while keeping the core ethos intact.

6. Balancing Scale with Soul

Toms scaled rapidly – selling tens of millions of shoes and operating in dozens of countries – which is commendable, but scaling a social enterprise comes with unique challenges. One is maintaining the authenticity of the mission as operations become complex and corporate.

Toms faced this when Bain took over; some feared the “soul” of Toms might be compromised. Mycoskie even took a sabbatical in 2012 to reflect on maintaining Toms’ culture amid growth.

Lesson: As a company grows, it must consciously cultivate its founding values within the organization. Toms did this by institutionalizing giving (Chief Giving Officer role, volunteer programs) so that even as new management came in, the ethos persisted.

The fact that in the creditors’ letter in 2019 the CEO reaffirmed commitment to giving indicates that Toms’ core purpose was so ingrained it survived a change of ownership.

Other companies can learn to embed mission into company structures (e.g., legally as Benefit Corporations, or via internal policies) to protect it during transitions.

Additionally, the balance means sometimes making tough choices – like reducing headcount or product lines to save the company, but doing so in a way that’s compassionate and true to values (Toms, for instance, likely tried to help laid-off employees and remained generous in charitable commitments even when finances were tight, donating $2M to COVID relief in a tough year, showing consistency in values).

7. The Importance of Adaptability and Resilience

Toms’ trajectory wasn’t smooth – it had highs of being a celebrated innovator and lows of near insolvency. Through it all, the company’s ability to pivot has been crucial.

From adjusting its model to switching target demographics, to leveraging e-commerce when retail faltered, Toms survived because it adapted.

Lesson: Markets change, crises happen – the companies that endure are those that remain flexible and resilient. This often means recognizing when your original strategy isn’t working as well and being brave enough to change it (even if it’s something as iconic as One-for-One).

It also means diversifying risk (product lines, channels, etc.) so that one hit doesn’t sink the whole ship. In Toms’ case, diversification into direct online sales cushioned the pandemic blow, a testament to earlier efforts to build that channel.

8. Legacy and Inspiration

Lastly, one cannot ignore the broader impact Toms has had on the business world. Toms catalyzed a movement – showing that a for-profit can be a vehicle for social change. Richard Branson cited Toms as an example of a business that “sells its ideal” not just its product.

Many young entrepreneurs credit Start Something That Matters (Mycoskie’s book) and the Toms story for inspiring them to launch social ventures.

Lesson: A single company’s approach can shift paradigms in an industry. The “Compassionate consumerism” wave in the 2010s owes a lot to Toms.

For other businesses, this highlights that doing good can be good business, and that trailblazing in corporate social responsibility can enhance brand legacy.

However, being a pioneer also means you encounter challenges first – as Toms did with model critiques and market changes – and how you handle those will define your long-term legacy. Toms’ willingness to share its journey (successes and failures openly) provides a playbook for others to build on.

In conclusion, Toms Shoes’ case is rich with learnings: it validates the concept that businesses can have profound social impact and commercial success simultaneously, while also cautioning that such models must continuously evolve and be managed with both heart and mind.

Other businesses can emulate Toms’ strengths – mission-driven branding, community engagement, product storytelling – and also heed its lessons – diversify products, maintain financial health, and be accountable for your impact.

As of 2025, Toms is writing its “chapter two,” and its story remains a seminal example of social entrepreneurship in practice – illustrating both the rewards of pioneering a new model and the responsibility that comes with sustaining it.