Tony's Chocolonely transformed from a Dutch journalist's investigative project into a $200+ million chocolate company by making supply chain transparency its core competitive advantage.

Founded in 2005 after journalist Teun van de Keuken exposed slavery in West African cocoa production, the company built a vertically integrated model that pays farmers 40% above Fairtrade premiums while maintaining competitive retail pricing.

The business operates on three strategic pillars:

- direct relationships with 8,942 cocoa farmers across Ghana and Ivory Coast

- aggressive transparency including publishing full supply chain data and acknowledging when slavery is discovered in their chain

- and a consumer brand built on storytelling rather than traditional food marketing.

Tony's reached profitability in 2013 and has grown revenue at approximately 25-30% annually since 2016. The company holds 18% market share in Netherlands chocolate and expanded to the United States in 2015, where it now generates roughly 20% of total revenue. Unlike most mission-driven food brands that exit to CPG conglomerates, Tony's remains independent with a governance structure designed to prevent acquisition by companies that do not meet their sourcing standards.

The model works because Tony's converted a cost center into a differentiation engine. While competitors treat ethical sourcing as a compliance checkbox, Tony's made it the entire product story. This case study examines how they built the operational infrastructure to deliver on that promise, the economics that make it sustainable, and the strategic decisions that allowed a mission-driven brand to scale without diluting standards.

Problem Context: Slavery in the Chocolate Industry

The global chocolate industry generates approximately $130 billion in annual revenue. Roughly 60% of the world's cocoa supply originates in West Africa, with Ivory Coast and Ghana producing 3.5 million tons combined.

The supply chain historically operated through a system of aggregators and middlemen that obscured farmer conditions from chocolate manufacturers and consumers.

In 2001, the Harkin-Engel Protocol was signed by major chocolate companies including Mars, Nestlé, and Hershey, committing to eliminate the worst forms of child labor from cocoa supply chains by 2005.

That deadline was missed and extended repeatedly.

A 2020 NORC study commissioned by the U.S. Department of Labor found that 1.56 million children were engaged in hazardous labor in cocoa production in Ivory Coast and Ghana, an increase from 2008/09 levels despite two decades of industry commitments.

The economic structure driving these outcomes is straightforward.

Cocoa farmers in West Africa earn an average of $0.78 per day according to Fairtrade International data.

This income sits well below the $2.16 per day living income benchmark established for rural Ghana and the $2.50 benchmark for Ivory Coast.

Farmers lack capital for hiring adult labor, investment in farm productivity, or sending children to school rather than farm work.

The certification systems meant to address these issues have failed to change outcomes at scale. Fairtrade and Rainforest Alliance certifications create premiums of $200 to $400 per metric ton above commodity pricing.

While this represents an improvement, it rarely reaches the income levels needed for farmers to operate without child labor. Additionally, certification costs and administrative complexity often exclude the smallest and poorest farmers from participation.

Three structural factors explain why these problems persist despite consumer awareness and corporate commitments.

- First, cocoa is a commodity crop where farmers have no pricing power and minimal ability to capture value beyond the farm gate.

- Second, supply chains fragment across dozens of intermediaries between farmer and manufacturer, making traceability nearly impossible under traditional procurement models.

- Third, the economic incentive structure rewards volume and cost reduction rather than farmer welfare or labor practices.

This was the industry context when Tony's Chocolonely entered the market.

The company's core thesis was that incremental improvements through certification schemes would not solve systemic problems.

The solution required direct relationships, radical transparency, and a willingness to redesign supply chain economics from the ground up.

Origin Story: From Journalism to Chocolate Manufacturing

Tony's Chocolonely originated from investigative journalism, not entrepreneurship. In 2002, Dutch journalist Teun van de Keuken produced a documentary series called "Keuringsdienst van Waarde" (Inspection Service of Value) that investigated consumer product supply chains.

One episode examined chocolate and uncovered extensive evidence of child slavery and forced labor in West African cocoa production.

Van de Keuken took an unusual approach to advocacy.

Rather than simply reporting the findings, he turned himself in to Dutch authorities in 2003, arguing that by purchasing and consuming chocolate produced with slave labor, he had violated laws against human trafficking and slavery.

He challenged prosecutors to either charge him or acknowledge that the legal system was complicit in allowing slavery-produced goods to be sold in the Netherlands.

Dutch authorities declined to prosecute.

The case received significant media attention but produced no policy changes or industry action. Van de Keuken concluded that journalism alone would not disrupt the economic incentives maintaining the existing system.

The response needed to be commercial.

In 2005, van de Keuken and a small team founded Tony's Chocolonely.

The name references both the founder and the company's position as the only chocolate manufacturer attempting to build a completely slave-free supply chain.

The original product was a single chocolate bar weighing 180 grams, intentionally oversized to stand out on retail shelves and signal differentiation from standard offerings.

The early strategy focused on proof of concept rather than scale.

Tony's identified a small cooperative in Ghana willing to work on direct contract terms. The company committed to paying Fairtrade minimum price plus a 40% premium, significantly above standard certification premiums.

This premium was designed to reach living income levels based on household economic modeling rather than arbitrary percentage increases over commodity prices.

From 2005 to 2010, Tony's operated as a mission-driven project with minimal commercial infrastructure.

Distribution was limited primarily to Netherlands specialty stores and direct sales through the company's website.

The product was positioned as activism in chocolate form, a purchase that directly funded an alternative supply chain model. Marketing relied heavily on media coverage of van de Keuken's original journalism and ongoing advocacy rather than traditional advertising.

The business model during this period was not sustainable.

Costs per bar were significantly higher than competitors due to small production volumes, premium farmer payments, and lack of manufacturing infrastructure.

Tony's contracted production to third-party manufacturers and functioned primarily as a brand and supply chain coordinator rather than an integrated chocolate company.

Two developments changed the trajectory.

First, consumer demand in the Netherlands exceeded initial projections.

The combination of strong brand story, distinctive packaging, and genuine product differentiation created word-of-mouth growth that allowed Tony's to secure wider retail distribution through Albert Heijn and other major Dutch supermarket chains.

Second, the company realized that manufacturing integration was necessary to control costs and maintain supply chain transparency.

In 2013, Tony's reached operating profitability for the first time.

Revenue was approximately €18 million.

The company had secured distribution in most major Dutch retailers and begun establishing the operational systems needed for geographic expansion.

The strategic question at this point was whether to remain a niche Netherlands brand with strong values or attempt to scale the model internationally while maintaining sourcing standards.

The decision to scale was based on impact logic rather than pure business growth.

If the goal was eliminating slavery from chocolate, a single-country brand serving 1-2% of the global market would not create sufficient pressure on industry incumbents to change practices.

The company would need to demonstrate that the model worked at meaningful scale across geographies and price points.

Business Model and Revenue Structure

Tony's Chocolonely operates as a premium chocolate brand with vertically integrated supply chain management. Revenue comes from wholesale distribution to retail partners and direct-to-consumer sales through the company website and branded stores.

The business reached approximately $220 million in revenue in 2022 based on publicly available financial statements filed in the Netherlands.

The product line centers on chocolate bars in distinctive unequally divided segments, representing the inequality in the chocolate industry.

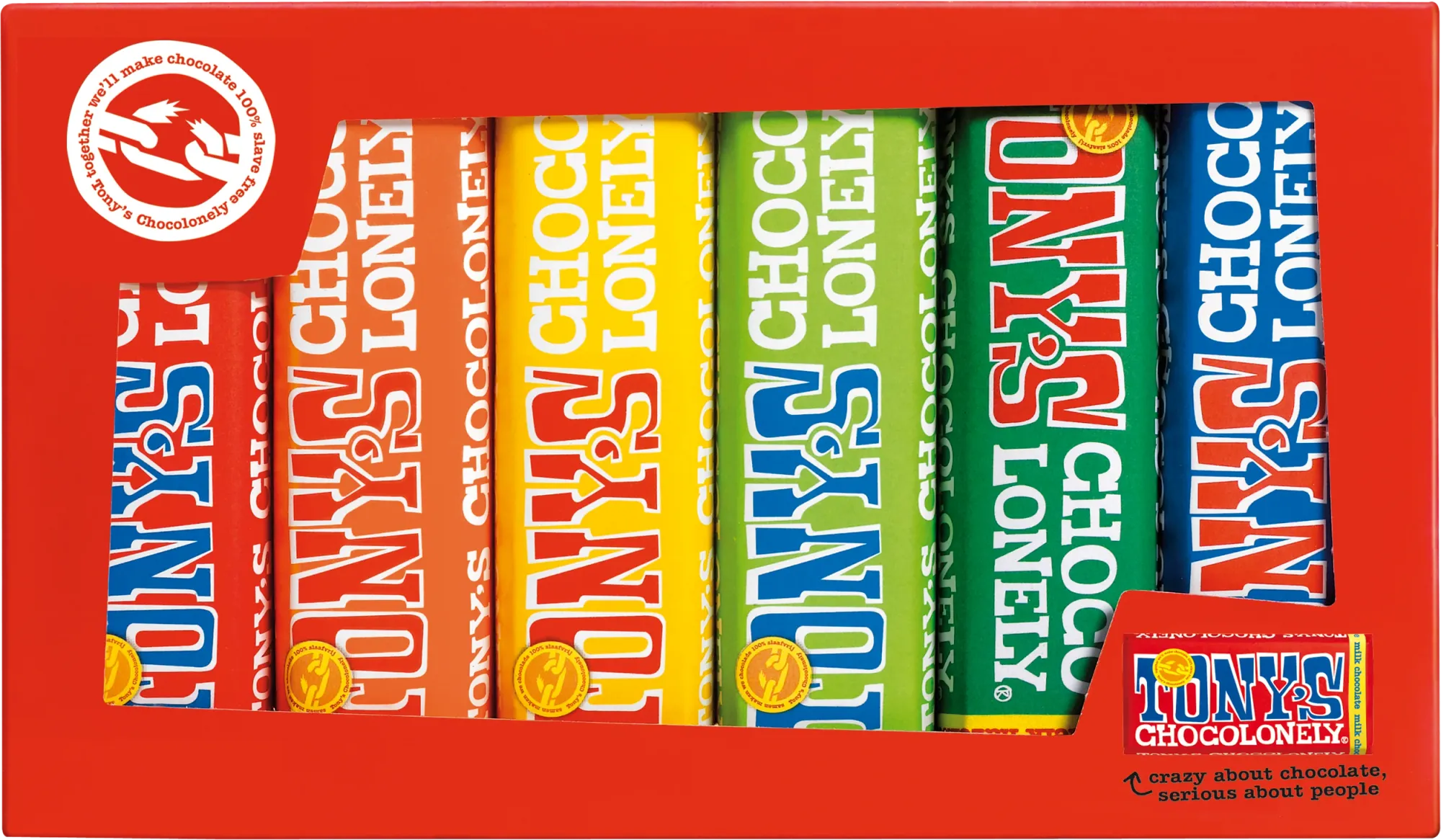

The standard range includes 15 flavors across milk, dark, and white chocolate categories, priced at €3.19 to €3.99 in Netherlands retail and $5.99 to $6.99 in U.S. markets.

This positions Tony's at a 40-60% premium over mass market brands like Hershey or Milka but below artisan chocolate brands that retail at $8-12 per bar.

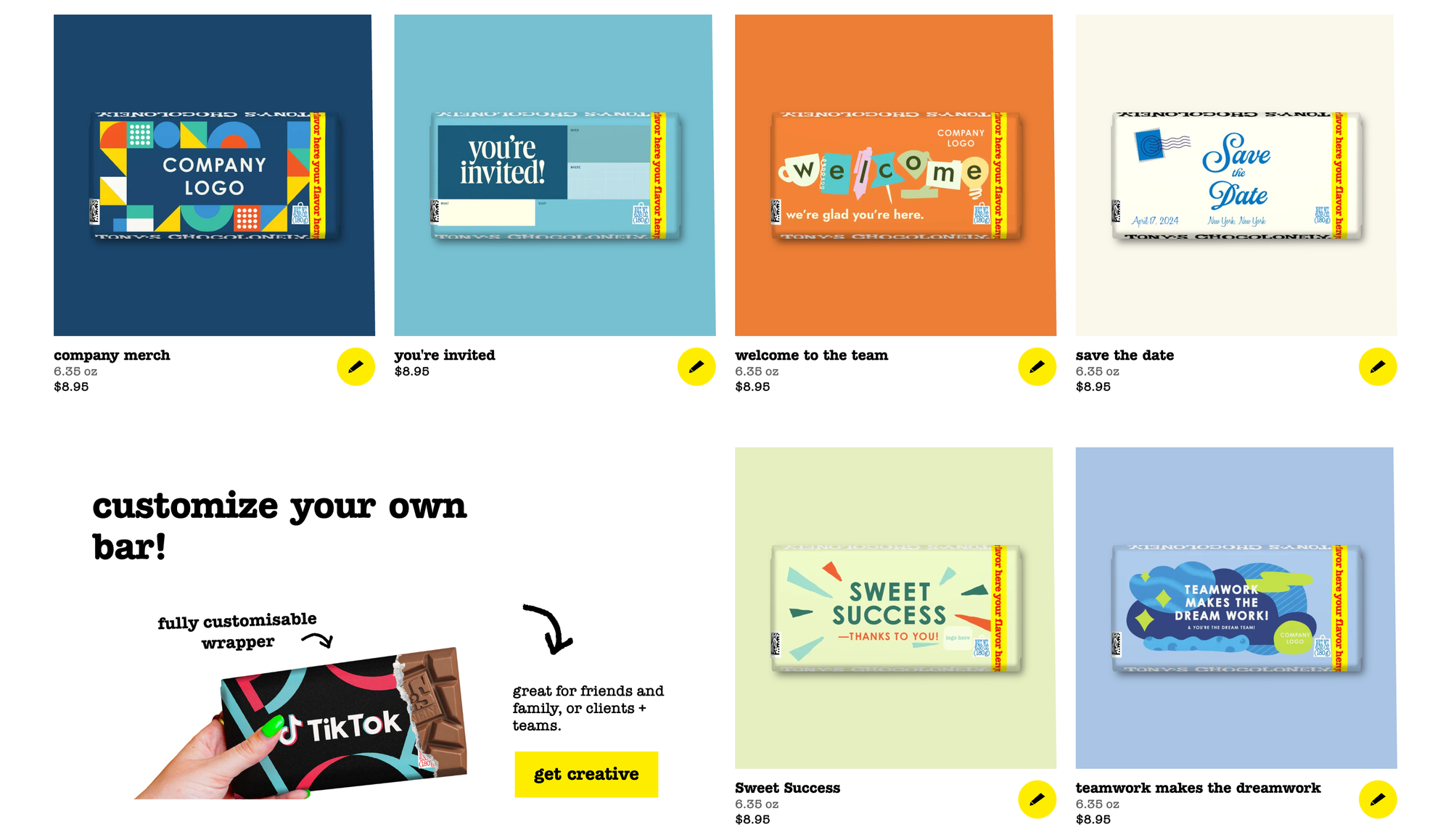

The company expanded beyond bars into related categories: chocolate-covered nuts and caramel products, seasonal gift boxes and limited editions, corporate gifting and custom bar programs, and co-branded products with partners like Ben & Jerry's ice cream.

These extensions maintain the core supply chain model while expanding addressable market and average transaction value.

Geographic revenue breaks down as follows based on 2021-2022 company reports: Netherlands represents approximately 55-60% of revenue, making Tony's the largest premium chocolate brand in the country with 18% total market share.

United States accounts for roughly 20% of revenue through distribution in Whole Foods, Target, REI, and specialty retailers. The remaining 20-25% comes from Belgium, Germany, United Kingdom, France, Sweden, and Finland.

Geographic Revenue Distribution

Based on 2021-2022 company reports

The United States market represents the highest growth rate but also the most challenging unit economics. Distribution costs are higher due to geography, brand awareness is lower requiring more marketing investment, and competition is more intense from both premium and mass market players.

Tony's addressed this through selective retail partnerships focused on retailers where the brand story aligns with customer values, like Whole Foods and REI, rather than pursuing mass distribution through Walmart or Kroger.

Gross margins sit at approximately 45-48% based on available financial data.

This is lower than typical premium food brands that target 50-60% gross margins, reflecting the higher cocoa costs from the direct farmer payment model.

The company maintains profitability through operational efficiency, relatively low marketing spend due to strong earned media and brand story, and premium pricing that consumers accept based on mission alignment.

Cost Structure Breakdown

Tony's Chocolonely vs. Mainstream Chocolate Brands

Key Differences

- Cocoa costs 60% higher: Tony's pays 35-40% vs. 20-25% for mainstream brands due to living income premiums

- Marketing costs 40% lower: Tony's spends 8-12% vs. 15-20% for mainstream brands through PR and advocacy instead of paid advertising

- Manufacturing similar: Both use contract manufacturing at comparable rates (10-15%)

- Distribution similar: Logistics costs are comparable at 12-15% of revenue

One significant financial decision was the choice to maintain manufacturing relationships with partners rather than building owned production facilities.

Tony's contracts with Barry Callebaut, one of the world's largest chocolate manufacturers, for production of its bars.

This creates lower capital requirements and allows the company to scale production without massive fixed cost investments.

The tradeoff is reduced margin capture and dependency on a manufacturing partner that also produces chocolate for competitors.

The direct-to-consumer channel generates approximately 8-10% of revenue but carries higher margins due to elimination of retail markups.

The company operates an e-commerce platform and several branded retail locations called "Tony's Super Stores" in Amsterdam and other cities.

These stores function as both revenue generators and brand experience centers that reinforce the mission story and supply chain transparency.

Corporate gifting and custom bar programs represent a growing revenue stream with favorable economics. Companies purchase customized bars for employee gifts, client appreciation, or event giveaways.

Minimum orders start at 100 bars with pricing at €4.50-6.00 per unit depending on volume and customization. This channel generates higher gross margins than retail while also creating brand exposure to new potential consumers.

The business model reflects a deliberate choice to compete on differentiation rather than cost.

Tony's cannot win on price against Mars or Nestlé given the structural cost disadvantages from farmer premiums and smaller scale.

The strategy instead focuses on creating a product where the supply chain story is inseparable from the brand, making price comparison less relevant for the target consumer.

This approach works in a market segment where consumers are willing to pay premiums for verifiable impact. The question long-term is how large that segment can grow and whether Tony's can maintain differentiation as more brands adopt transparency and ethical sourcing claims.

Supply Chain Innovation: The Five Sourcing Principles

Tony's Chocolonely built its supply chain on five principles designed to address the structural issues that enable slavery and child labor in cocoa production.

These principles function as non-negotiable operating requirements rather than aspirational goals.

Principle 1: Traceable Cocoa Beans

Every cocoa bean must be traceable to the specific cooperative and, where possible, the individual farmer who grew it. This requires Tony's to work only with cooperatives that maintain farmer registries and can segregate Tony's beans throughout processing and transport.

The implementation means Tony's cannot source from commodity markets or aggregated supply where beans from multiple origins are mixed.

All cocoa comes from identified cooperatives in Ghana and Ivory Coast that Tony's has direct contracts with.

The company maintains a digital traceability system that tracks each shipment from cooperative to port to processing facility to finished product.

This traceability creates cost overhead.

Segregated supply chains require separate storage, transport, and processing from commodity flows. Cooperatives must maintain additional record-keeping systems.

The premium Tony's pays includes compensation for these administrative requirements.

The benefit is visibility.

When child labor or forced labor is discovered in the supply chain, Tony's can identify exactly which farms are involved and take corrective action at the source level rather than issuing general statements about improving practices.

Principle 2: Higher Price Paid to Farmers

Tony's pays farmers the Fairtrade minimum price plus an additional 40% premium. In practical terms, this means $2,800 to $3,200 per metric ton compared to commodity prices that fluctuate between $2,200 and $2,600 per ton and Fairtrade certification premiums that add $200-240 per ton.

The 40% premium was calculated based on living income modeling that estimates the revenue a cocoa farming family needs to cover basic necessities, school fees, healthcare, and farm maintenance.

The calculation factors in average farm size, cocoa yield per hectare, household size, and local cost of living data.

This pricing is guaranteed regardless of commodity market fluctuations. When global cocoa prices drop, Tony's maintains the premium floor. When prices spike, the premium remains locked, though farmers benefit from the higher base price.

The economic logic is that farmers earning living income are less likely to use child labor, more able to invest in farm productivity, and more willing to maintain long-term relationships with buyers who offer stable pricing.

The data from Tony's cooperatives shows higher school enrollment rates and lower child labor incidence compared to national averages, though direct causation is difficult to isolate from other program interventions.

Principle 3: Strong Farmers

Tony's invests in farmer productivity through training, access to farm inputs, and cooperative strengthening. The company partners with local NGOs and agricultural extension programs to deliver training on pest management, soil health, pruning techniques, and diversification crops.

The business case is straightforward. Higher yields per hectare increase farmer income even with stable per-ton pricing. Farmers who earn more are less dependent on any single buyer and more able to weather commodity price volatility or climate shocks.

Tony's also provides advance payment to cooperatives before harvest to finance input purchases and working capital needs. This addresses a chronic challenge in smallholder agriculture where farmers lack access to credit and must sell immediately after harvest when prices are lowest.

Cooperative strengthening includes support for governance structures, financial management training, and group purchasing of inputs. Stronger cooperatives negotiate better terms with traders, access certification programs more easily, and provide better services to member farmers.

Principle 4: Long-Term Commitment

Tony's signs five-year contracts with cooperatives rather than the one-year or spot market purchases typical in the industry. These contracts include minimum volume commitments and fixed premium pricing structures.

Long-term contracts allow farmers and cooperatives to plan investments, access credit using purchase agreements as collateral, and make multi-year decisions about farm management.

The stability reduces risk and creates economic conditions where farmers can optimize for long-term productivity rather than short-term survival.

From Tony's perspective, long-term relationships reduce supply chain volatility, ensure consistent quality, and create partnership conditions where cooperatives invest in meeting Tony's traceability and labor standards.

The commitment is mutual. Tony's cannot easily switch suppliers if a cooperative's beans are lower quality or if pricing becomes uncompetitive. The tradeoff is that deep relationships create problem-solving partnerships rather than transactional supply arrangements.

Principle 5: Quality and Productivity

Higher farmer income must come from both better pricing and improved productivity. Tony's works with cooperatives to increase yield per hectare through better farming practices, access to quality seedlings, pest and disease management, and soil health programs.

Ghana cocoa yields average 400-500 kilograms per hectare.

Tony's cooperative partners achieve 600-800 kilograms per hectare through improved practices.

This yield increase translates directly to higher farmer income without requiring additional land cultivation.

The company also focuses on quality premiums.

Higher quality beans command better prices and reduce waste in processing. Training programs cover fermentation techniques, drying processes, and post-harvest handling that improve bean quality and reduce defects.

These five principles create a sourcing model that costs 15-20% more than conventional chocolate supply chains but delivers verifiable outcomes on labor conditions, farmer income, and supply chain transparency.

The model only works commercially because Tony's built a brand where consumers understand and value these differences.

Farmer Economics and Direct Relationships

Tony's works with 8,942 farmers across Ghana and Ivory Coast through five cooperative partnerships. These cooperatives range from 800 to 2,500 member farmers and are located in cocoa-growing regions where Tony's has maintained relationships for 8 to 15 years.

The farmer economics work as follows.

An average smallholder cocoa farmer in Tony's network manages 2 to 3 hectares of cocoa. Under the Tony's pricing model of Fairtrade minimum plus 40% premium, a farmer producing 600 kilograms per hectare across 2.5 hectares would generate:

- 1,500 kilograms total production

- $3,000 per ton average price

- $4,500 gross revenue

After costs for inputs, labor, and cooperative fees of approximately $1,200 to $1,500, net income reaches $3,000 to $3,300 annually.

This translates to roughly $8.20 to $9.00 per day for a household, above the $2.16 living income benchmark when spread across average household size.

This calculation assumes reasonable yields and no major crop losses from disease or weather. In practice, farmer incomes vary significantly based on farm productivity, household size, and other income sources beyond cocoa.

Tony's data shows that approximately 60% of cooperative member farmers reach living income levels, 30% fall below but are moving toward the benchmark, and 10% remain well below despite the premium pricing due to very small farms, low yields, or large dependent households.

The direct relationship model means Tony's field staff visit cooperatives quarterly to review production forecasts, discuss quality issues, and monitor child labor remediation programs.

This frequency is significantly higher than the annual or biannual visits typical in certified supply chains.

When child labor is discovered through monitoring systems, Tony's protocol requires immediate remediation including removing children from hazardous work, enrolling them in school with fees paid through cooperative community funds, and providing household income support if the child's labor was economically necessary for the family.

The company publicly reports these incidents in its annual FAIR report rather than hiding violations.

From 2020 to 2022, Tony's monitoring systems identified 253 cases of child labor across its cooperative network.

All cases were in the "hazardous work" category rather than forced labor or trafficking. Remediation actions were implemented in 237 cases, with 16 cases requiring ongoing intervention due to complex household circumstances.

This transparency is unusual in the chocolate industry, where most companies report only aggregated metrics or make claims about "working toward" elimination of child labor without acknowledging current incidence rates.

Tony's position is that honest reporting builds credibility and creates accountability pressure that drives systemic improvement.

The farmer relationships extend beyond pricing and monitoring to include support services.

Tony's provides access to agronomists for technical assistance, financial literacy training through cooperative programs, advance payment systems that reduce farmer dependency on informal lenders, and child labor monitoring and remediation services.

One significant challenge is scale limits. The direct relationship model requires intensive management and limits how quickly Tony's can expand cocoa sourcing.

Adding new cooperatives takes 18 to 24 months of relationship development, traceability system implementation, and farmer training before beans can be integrated into Tony's supply chain.

This creates a constraint on revenue growth. Tony's can only expand sales as fast as it can responsibly expand sourcing.

The company addresses this through multi-year planning that sequences new cooperative partnerships with expected demand growth, but it means Tony's cannot pursue the aggressive expansion timelines common in consumer packaged goods companies.

Brand Strategy and Consumer Positioning

Tony's built its brand on three core elements: a bold visual identity with distinctive packaging, radical transparency about supply chain challenges, and storytelling that positions chocolate consumption as activism.

The packaging design features bright colors, unequally divided chocolate segments, and wrapper designs that include mission messaging and supply chain details.

The unequal division represents inequality in the chocolate industry and creates a memorable unboxing experience that generates social sharing and word-of-mouth.

Each wrapper includes the mission statement, information about the cooperative that grew the cocoa, and instructions for consumers to join the movement by choosing slave-free chocolate and pressuring other brands to improve practices.

This packaging as communication strategy turns every purchase into a brand education moment.

The color palette uses primary colors in unexpected combinations: bright red, purple, yellow, and pink. This creates shelf presence in retail environments dominated by brown and gold packaging from traditional chocolate brands.

The design signals differentiation before consumers read any text or understand the mission story.

Tony's invests heavily in brand experience beyond the product. The company operates Tony's Super Stores in Amsterdam and other cities that function as chocolate museums and brand centers.

Visitors can see supply chain information, taste samples, and learn about cocoa farming conditions. These stores generate revenue but primarily serve brand building and consumer education goals.

The company also created the "Tony's Open Chain" program in 2018, making its supply chain model available to other chocolate brands.

Any company can adopt Tony's five sourcing principles and access the same cooperative relationships and traceability systems. The licensing is free; brands pay only the actual cost premiums for the sourcing model.

This open source approach seems counterintuitive from a competitive standpoint. Tony's is giving away its primary differentiation to potential competitors.

The strategic logic is that the mission is ending slavery in chocolate, not building the largest chocolate brand. If other companies adopt the model, industry practices improve even if Tony's loses unique positioning.

Partners in the Open Chain include Ben & Jerry's, Albert Heijn private label, and several smaller chocolate brands.

These partnerships validate the sourcing model and create industry momentum toward higher standards, while also generating consulting revenue for Tony's through setup and ongoing monitoring services.

The marketing strategy relies on earned media, partnerships, and consumer advocacy rather than traditional advertising.

Tony's media coverage comes from the founder's journalism background and the company's willingness to make bold public statements about industry failures. The brand generates significant press coverage by publicly calling out major chocolate companies for false or misleading ethical sourcing claims.

This aggressive transparency extends to acknowledging Tony's own failures. The company's annual FAIR report includes detailed data on child labor incidents discovered in its supply chain, production errors, and areas where the company fell short of goals. This honesty builds trust and differentiates Tony's from competitors who make perfection claims.

Social media strategy focuses on education and movement building rather than product promotion. Content includes farmer stories, supply chain explainers, industry critique, and calls to action for consumers to pressure other brands.

The tone is optimistic but direct, avoiding the cynicism common in activist marketing or the excessive cheerfulness typical of consumer packaged goods brands.

The brand positioning creates a specific customer profile: values-driven consumers willing to pay premium prices for verifiable impact, people who see consumption choices as political and ethical acts, and customers who appreciate transparency including acknowledgment of problems and failures.

This positioning limits total addressable market. Tony's will not appeal to price-sensitive consumers or people who view chocolate as an impulse purchase rather than a meaningful choice. The company accepted this constraint as necessary to maintain pricing and sourcing standards that deliver real impact.

Geographic Expansion and Market Performance

Tony's expansion strategy prioritized markets where consumer values and retail infrastructure aligned with the brand story and premium pricing model.

The Netherlands remains the core market with 18% share of total chocolate sales and market leadership in the premium segment.

Growth in Netherlands has slowed to single digits as the brand reaches saturation in its core demographic. The focus shifted to building presence in larger markets that could drive meaningful revenue growth.

United States entry began in 2015 through specialty retail including Whole Foods Market, select Target locations, and outdoor retailers like REI.

The U.S. strategy targeted retailers where customer values aligned with Tony's mission and where premium pricing would not be a barrier. Distribution expanded gradually to approximately 12,000 retail locations by 2022.

U.S. market challenges included limited brand awareness requiring higher marketing investment, intense competition from both premium brands like Theo Chocolate and mass market players with ethical sourcing claims, and distribution costs that impacted margins given the distance from European production facilities.

The company addressed awareness through partnerships with aligned brands like Ben & Jerry's for co-marketing campaigns, active social media presence focused on supply chain education, and experiential marketing at events and festivals where the target demographic gathers.

European expansion focused on markets with developed premium food segments and consumer interest in ethical consumption: Belgium, Germany, United Kingdom, and Scandinavia. These markets shared similar retail dynamics to Netherlands and required less consumer education about the value proposition.

Market performance varies significantly by region.

Netherlands revenue growth runs at 5-8% annually as the brand approaches market saturation.

United States growth sits at 30-40% annually from a smaller base as distribution expands and awareness increases.

Other European markets show 15-25% growth as retail penetration increases.

The geographic expansion creates operational complexity. Tony's must manage retail relationships across multiple countries with different regulations, languages, and distribution systems.

The company cannot simply export the Netherlands playbook given differences in retail concentration, consumer preferences, and competitive dynamics.

One strategic decision was maintaining consistent pricing across markets rather than localizing to competitive conditions.

A bar costs roughly the same in the U.S., Netherlands, and Germany when accounting for currency exchange.

This simplifies operations and preserves brand positioning but may limit growth in price-sensitive markets.

Distribution strategy remains selective.

Tony's is available in approximately 20,000 retail locations globally compared to mass market brands present in 200,000+ locations.

The company deliberately chooses not to pursue mass distribution through discount retailers or convenience stores where the brand story cannot be effectively communicated and price competition would pressure margins.

This selective distribution maintains brand equity but limits revenue potential. The tradeoff is that Tony's preserves pricing power and avoids the promotional discounting common in mass market food retail.

Organizational Structure and Governance

Tony's Chocolonely operates as a private company with a governance structure designed to protect mission integrity and prevent acquisition by companies that do not meet its sourcing standards.

The company is structured as Tony's Chocolonely B.V., a Dutch private limited company, with a separate foundation called Stichting Tony's Chocolonely Foundation that holds control over key decisions.

This foundation structure is common in European social enterprises and creates a mechanism to prioritize mission over profit maximization.

The foundation holds certain governance rights including approval required for any sale or acquisition of the company, veto power over changes to the five sourcing principles, and authority to appoint foundation board members who are independent of company management.

This structure makes a traditional exit to a major food conglomerate nearly impossible unless the acquirer commits to maintaining Tony's sourcing standards across its entire chocolate portfolio.

Since that would require Mars, Nestlé, or Mondelez to fundamentally restructure their supply chains at massive cost, acquisition is effectively blocked.

The employee structure is relatively lean at approximately 200 full-time employees globally. The team is organized into product development and sourcing, marketing and brand, sales and distribution, impact and monitoring, and operations and finance.

Company culture emphasizes the "Serious Fun" principle: the work is serious because slavery and farmer poverty are serious, but the approach should be joyful and energizing rather than grim. This manifests in office design, internal communications, and the brand voice that manages to address dark industry realities while maintaining optimism.

Compensation and incentive structures include standard salary and benefits plus an annual "Choco Bonus" tied to both financial performance and impact metrics.

Key performance indicators include revenue and margin targets, farmer income levels in cooperative partnerships, child labor incident reduction, and supply chain transparency measures.

This dual incentive structure attempts to align employee performance with both commercial success and mission outcomes. The challenge is that some goals may conflict, such as when expanding sourcing to new cooperatives reduces short-term margins but improves long-term impact.

Impact Measurement and Transparency Standards

Tony's publishes an annual FAIR report that documents progress on mission goals and details failures and setbacks alongside successes.

The 204/2025 report is 291 pages and includes data on farmer income, child labor incidents, cocoa traceability, and cooperative development.

The measurement framework tracks four key outcomes:

Farmer Income: In 2023/24, Tony's paid 44% above the government-set farmgate price in Côte d'Ivoire and 18% above the farmgate price in Ghana. 20,296 farmers (+14.4% YoY) now receive the Living Income Reference Price (LIRP) for cocoa sold through Tony's Open Chain.

For the 2024/25 season, an added emergency productivity boost was implemented to further support farmers in achieving a living income.

While the previous 2022 data showed 61% of farmers reaching living income benchmark, the company now emphasizes that enabling farmers to earn a living income "relies heavily on the industry adopting our proven sourcing model" so that "more farmers sell more beans at this higher price for the long term."

Child Labor Incidence: The 2023/24 figures show child labor prevalence at long-term partner cooperatives (3+ years) decreased from 4.4% to 3.9% within 12 months. This compares to an industry average of 46.7%.

During the reporting period, 1,718 children were remediated out of child labor situations. Tony's has implemented CLMRS (Child Labor Monitoring and Remediation System) in every household of all farmer members across its partner cooperatives. The company explicitly states it reports and remediates "every child labor case we find, rather than look the other way."

Supply Chain Traceability: In the 2024/25 operating year, Tony's achieved 100% traceability of its cocoa beans, with all beans purchased from GPS-mapped farms at premium prices. The company uses the digital "Bean Tracker" platform that identifies which farmers supplied what percentage of each shipped container.

For deforestation verification, 26,536 cocoa farms (99.95% of supply chain) are verified deforestation-free, with 14 farms representing the remaining 0.05% still being resolved. The most recent report claims 99.9% verified deforestation-free supply.

Farmer Productivity: Cooperatives working with Tony's Open Chain reported crop losses of only 11%, nearly half the industry average of approximately 20% during the 2024/25 season.

This resilience allowed Tony's to increase cocoa bean orders to 30,000 metric tons (+71% YoY) for the current season. The company's cocoa sourcing through Tony's Open Chain had 95% lower emissions in Côte d'Ivoire and 87% lower emissions in Ghana than most other cocoa from the same region, largely because the supply chain has been confirmed deforestation-free (deforestation being the primary driver of cocoa-related emissions).

This level of transparency is unusual in impact reporting, where most companies emphasize positive metrics and avoid detailed disclosure of problems. Tony's position is that honest reporting is necessary for accountability and that acknowledging failures builds trust rather than undermining it.

The measurement approach uses third-party verification for key data points. KIT Royal Tropical Institute conducts farmer income surveys using independent enumerators.

Child labor monitoring is implemented by local NGOs trained in International Labour Organization protocols. These external verification systems reduce the risk of biased reporting or data manipulation.

Tony's also tracks industry influence metrics including number of companies joining Tony's Open Chain, media coverage of chocolate industry labor issues where Tony's is cited, and policy advocacy outcomes such as mandatory human rights due diligence laws influenced by Tony's transparency work.

The challenge with impact measurement is attribution. Tony's can document that farmers in its supply chain earn higher incomes and send children to school at higher rates, but isolating which outcomes result from Tony's pricing versus cooperative training programs versus broader economic trends is difficult.

The company addresses this by reporting observed outcomes rather than claiming credit for specific changes. The framing is "farmers in our supply chain experience these outcomes" rather than "our intervention caused these improvements."

Challenges, Failures, and Ongoing Issues

Tony's has encountered significant challenges in executing its model at scale, some structural and some self-inflicted.

Scaling Constraint: The direct relationship model limits growth speed. Adding new cooperatives requires 18 to 24 months of relationship building and system implementation.

This created situations where demand for Tony's chocolate outpaced available supply from verified cooperatives, forcing the company to turn down distribution opportunities or accept slower growth than investor expectations.

Manufacturing Dependency: Contracting production to Barry Callebaut creates dependency on a partner that also produces chocolate for companies with lower sourcing standards.

This relationship drew criticism from activists who argued Tony's should not work with manufacturers that enable slavery in other parts of their business. Tony's response was that building owned manufacturing was capital prohibitive and that working with Barry Callebaut while pushing for better standards across all their production created more impact than isolation.

Child Labor Persistence: Despite paying premium prices and implementing monitoring systems, child labor has not been eliminated from Tony's supply chain.

The incidence rate of 2.8% represents meaningful improvement over industry averages but falls short of the zero-tolerance goal. This exposes the reality that pricing alone does not solve poverty-driven child labor when farmers face health emergencies, crop failures, or other economic shocks that pressure them to use all available family labor.

Market Saturation in Netherlands: With 18% market share, Tony's is approaching the ceiling of consumers willing to pay premium prices for ethical chocolate in its home market.

Growth requires expanding to new geographies where the brand must compete without the first-mover advantage and media attention that drove Netherlands success.

Competitive Response: Major chocolate companies launched ethical sourcing programs and made sustainability claims that confused consumers and diluted Tony's differentiation.

Mars' Sustainable Cocoa Initiative, Nestlé's Cocoa Plan, and Hershey's Learn to Grow program all use language about improving farmer welfare and reducing child labor. While these programs deliver less impact than Tony's model, they create perception that mainstream brands are equally responsible, reducing Tony's pricing premium justification.

Open Chain Risk: Making the sourcing model available to competitors through Tony's Open Chain potentially commoditizes the company's primary differentiation.

If multiple brands adopt identical sourcing standards, Tony's loses unique positioning and must compete on taste, packaging, and marketing rather than mission. The company accepted this risk as necessary to achieve industry transformation but it remains a strategic vulnerability.

Geographic Complexity: Expanding to markets with different languages, regulations, and retail dynamics created operational challenges. Marketing messages that resonated in Netherlands fell flat in Germany.

Distribution economics that worked in compact Netherlands became unprofitable in the United States. The company had to build country-specific strategies while maintaining global brand consistency.

Governance Tensions: The foundation structure that protects mission creates decision-making complexity and can slow commercial pivots. When management wants to pursue growth strategies that push boundaries on sourcing principles, foundation oversight creates friction. This is intentional but slows decision velocity compared to traditional corporate structures.

Cost Pressure: Maintaining 15-20% higher cocoa costs requires consistent premium pricing. When competitors discount or when economic conditions make consumers more price sensitive, Tony's cannot easily respond without cutting sourcing standards or accepting margin compression.

One notable failure was the 2020 attempt to expand into professional bakery and food service channels. Tony's developed bulk chocolate products for use by bakeries and restaurants, thinking this would expand impact by getting slave-free chocolate into more consumer touchpoints.

The initiative failed because food service buyers prioritized price and consistency over sourcing story, and Tony's lacked the account management infrastructure for B2B sales. The company shut down the program after 18 months and refocused on consumer retail.

These challenges illustrate that mission-driven business models face inherent tensions between impact goals and commercial sustainability. Tony's navigates these by accepting slower growth, higher costs, and strategic constraints that pure profit-maximizing competitors do not face.

Lessons Learned and Key Takeaways

Tony's Chocolonely offers several strategic lessons for companies attempting to build profitable businesses that deliver measurable social or environmental impact.

Make the cost center the differentiation engine. Tony's converted what most companies treat as a cost (ethical sourcing) into its primary competitive advantage. The 15-20% cost premium for verified slave-free cocoa became the entire brand story rather than a margin problem to minimize. This only works when the cost creates customer value that justifies premium pricing.

Transparency including failures builds credibility. Most impact brands emphasize successes and hide problems. Tony's publishes detailed data on child labor incidents, farmer income shortfalls, and operational failures. This honesty differentiates the brand from competitors making perfection claims and creates trust with consumers who appreciate realistic reporting over marketing promises.

Vertical integration of impact is necessary at scale. Tony's cannot rely on certification systems or third-party audits to verify supply chain claims. The company built direct relationships, monitoring systems, and traceability infrastructure to ensure outcomes match brand promises. This requires operational complexity and cost but delivers differentiation that certifications cannot provide.

Mission protection requires governance design. The foundation structure prevents acquisition by companies that would not maintain sourcing standards. This blocks the typical CPG exit path but protects long-term mission integrity. Impact brands planning for scale should design governance that makes mission drift structurally difficult rather than relying on values statements.

Industry transformation requires open source. Tony's made its supply chain model available to competitors through Tony's Open Chain. This seems to reduce competitive advantage but accelerates industry change and makes individual company success less critical to achieving mission goals. Impact brands should consider when proprietary advantages conflict with achieving systems change.

Premium pricing works for a limited segment. Tony's pricing at 40-60% above mass market brands appeals to values-driven consumers willing to pay for verified impact. This segment is real but limited, creating growth constraints. Impact brands must decide whether to remain premium and niche or pursue volume through different positioning.

Brand story must match operational reality. Tony's can tell its story aggressively because the sourcing model, transparency reporting, and traceability systems deliver what the brand promises. Many impact brands over-claim relative to operational capacity, creating reputational risk when gaps emerge. The brand story should match what the operations can reliably deliver.

Direct farmer relationships create supply constraints. The time required to develop new cooperative partnerships limits how fast Tony's can scale revenue. This creates tension with investor growth expectations but ensures quality and prevents dilution of sourcing standards. Impact brands should design supply chain development timelines that sequence with revenue growth plans.

Geographic expansion requires market-specific strategies. What worked in Netherlands does not automatically translate to the United States or Germany. Distribution channels, competitive dynamics, and consumer awareness differ significantly. Impact brands need country-specific approaches while maintaining global brand consistency.

Child labor elimination requires more than pricing. Despite paying 40% premiums, Tony's has not eliminated child labor from its supply chain. Poverty-driven labor use persists when families face economic shocks. This demonstrates that pricing interventions alone do not solve systemic poverty and that comprehensive programs addressing education, healthcare, and economic stability are necessary.

The Tony's model proves that mission-driven consumer brands can achieve significant scale and profitability while maintaining high impact standards.

The company reached $250+ million revenue while paying farmers living income prices and implementing radical supply chain transparency. This combination is rare in impact business and demonstrates that the tradeoff between profit and impact is often overstated.

However, the model also shows real constraints.

Growth is slower than traditional consumer brands due to supply chain development timelines. Costs are structurally higher due to sourcing premiums.

The addressable market is limited to consumers willing to pay premium prices.

Operational complexity increases with the need for monitoring systems and direct farmer relationships.

These constraints are not failures but design choices. Tony's optimized for impact and credibility rather than maximum growth and profitability.

The result is a business that delivers meaningful outcomes for farmers while remaining commercially sustainable.

For entrepreneurs and operators building impact-driven consumer brands, Tony's demonstrates that the key decisions are what constraints to accept in service of mission goals and how to design operations that turn impact investments into competitive advantages rather than cost burdens.