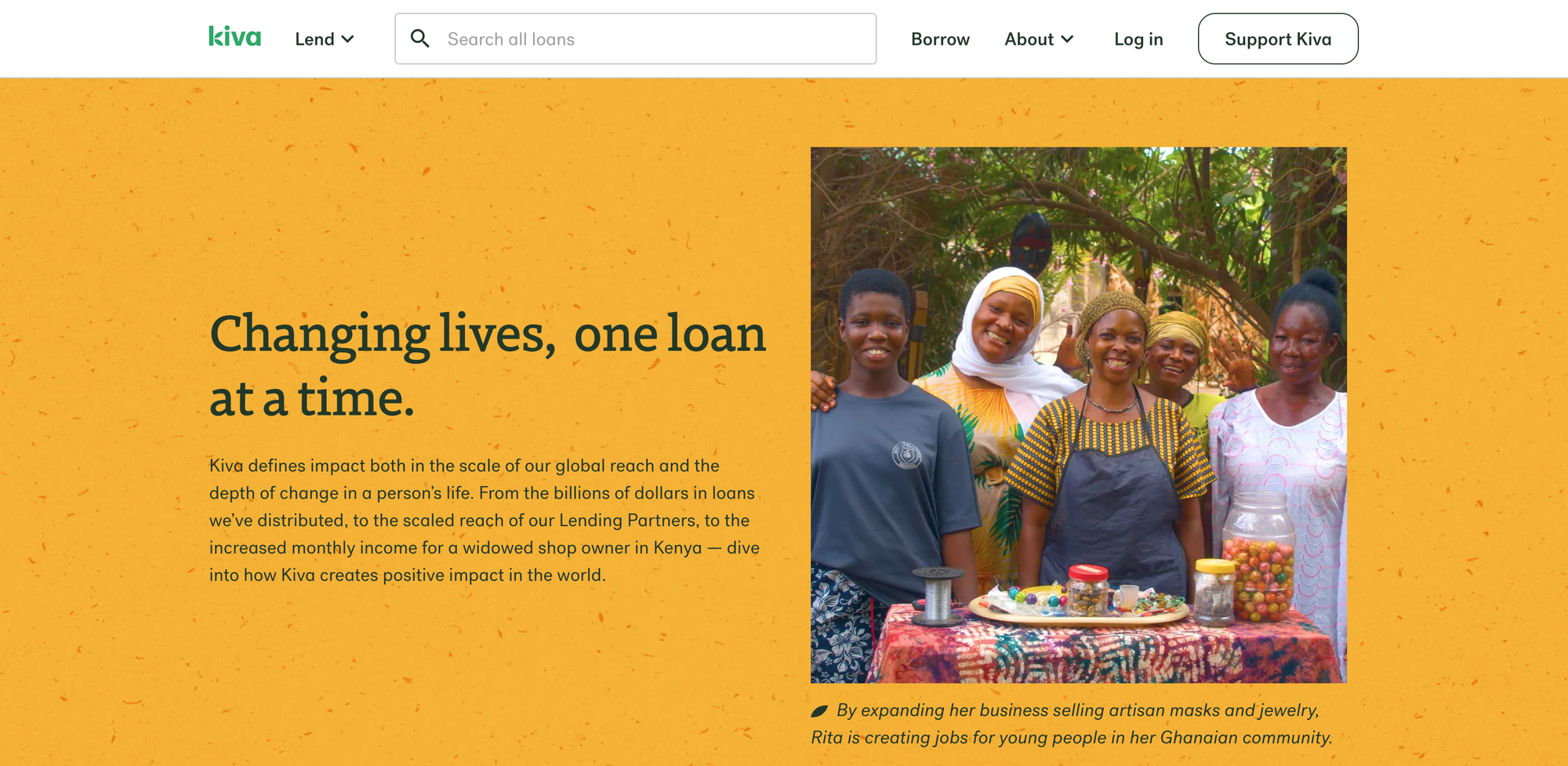

Kiva is a nonprofit microfinance platform founded in 2005 and headquartered in San Francisco, with a mission to expand financial access to underserved communities through crowdfunded micro-loans.

Using a website that connects individual lenders (often contributing as little as $25) to low-income borrowers around the world, Kiva pioneered person-to-person microlending for social good.

Over two decades, the organization has grown from a small startup into a global institution: as of 2025, Kiva’s community of 2+ million lenders has funded over $2.4 billion in loans for approximately 5.6 million borrowers across more than 90 countries.

Kiva’s primary programs center on its online lending platform, complemented by initiatives like Kiva U.S. (0% interest loans for American entrepreneurs) and Kiva Capital (impact investment funds).

This growth was enabled by strategic partnerships – for example, PayPal has processed every Kiva loan transaction free of charge, saving significant costs, and early grants from philanthropies such as the Omidyar Network (a 2010 $5 million commitment) helped Kiva scale its technology and enter new markets.

Kiva’s impact is notable both in scale and focus. Roughly 80% of Kiva loans go to women borrowers, advancing gender inclusion in finance. Its loans target a range of needs, from small business and agriculture to education, clean energy, and refugee support, reflecting a broad approach to poverty alleviation.

Outcomes data indicate positive benefits: in 2024, an independent survey found nearly 90% of borrowers reported improved quality of life, and 8 in 10 increased their income after receiving a Kiva-supported loan.

At the same time, Kiva maintains a high loan repayment rate of around 96% historically, thanks to careful due diligence on field partners and borrowers.

Financially, Kiva operates on a hybrid funding model. The loan capital is crowd-sourced from individual lenders and recycled; operating costs are covered primarily by voluntary donations (tips) from these lenders, which account for over two-thirds of revenue, supplemented by grants, corporate/foundation donations, and nominal fees from certain field partners.

This unique model has allowed Kiva to ensure that 100% of every loan dollar goes to borrowers, while still sustaining operations.

Kiva’s annual operating budget has grown to roughly $35 million (FY2024), and it consistently directs about 75–80% of expenses to programs (with the remainder in administration and fundraising), a level that earned it a 4-star Charity Navigator rating for financial stewardship.

The case of Kiva provides a realistic look at both the promise and pitfalls of microfinance in practice, informing how others might harness crowdfunding and fintech for social impact in a responsible, inclusive way.

Organizational Background and History

Founding and Early Inspiration

Kiva was founded in 2005 by Matt Flannery and Jessica Jackley, a pair of social entrepreneurs who conceived the idea after working in East Africa and witnessing the potential of microfinance at the grassroots level.

Inspired by a lecture from Dr. Muhammad Yunus (the Nobel Prize-winning founder of Grameen Bank), they set out to create a platform that would allow anyone with an internet connection to lend $25 or more to support a low-income entrepreneur abroad.

The name “Kiva” means “unity” in Swahili, reflecting the founders’ vision of connecting people through lending. In March 2005, Kiva made its very first loan: $500 to a fishmonger in Uganda, which the borrower used to expand her small business.

By the end of Kiva’s first full year, the website had facilitated about $1 million in loans, signaling strong public enthusiasm for this new peer-to-peer microcredit model.

The founding mission was straightforward yet ambitious – “to connect people through lending to alleviate poverty”, essentially crowd-sourcing capital to underserved entrepreneurs who lacked access to traditional finance.

Growth and Milestones

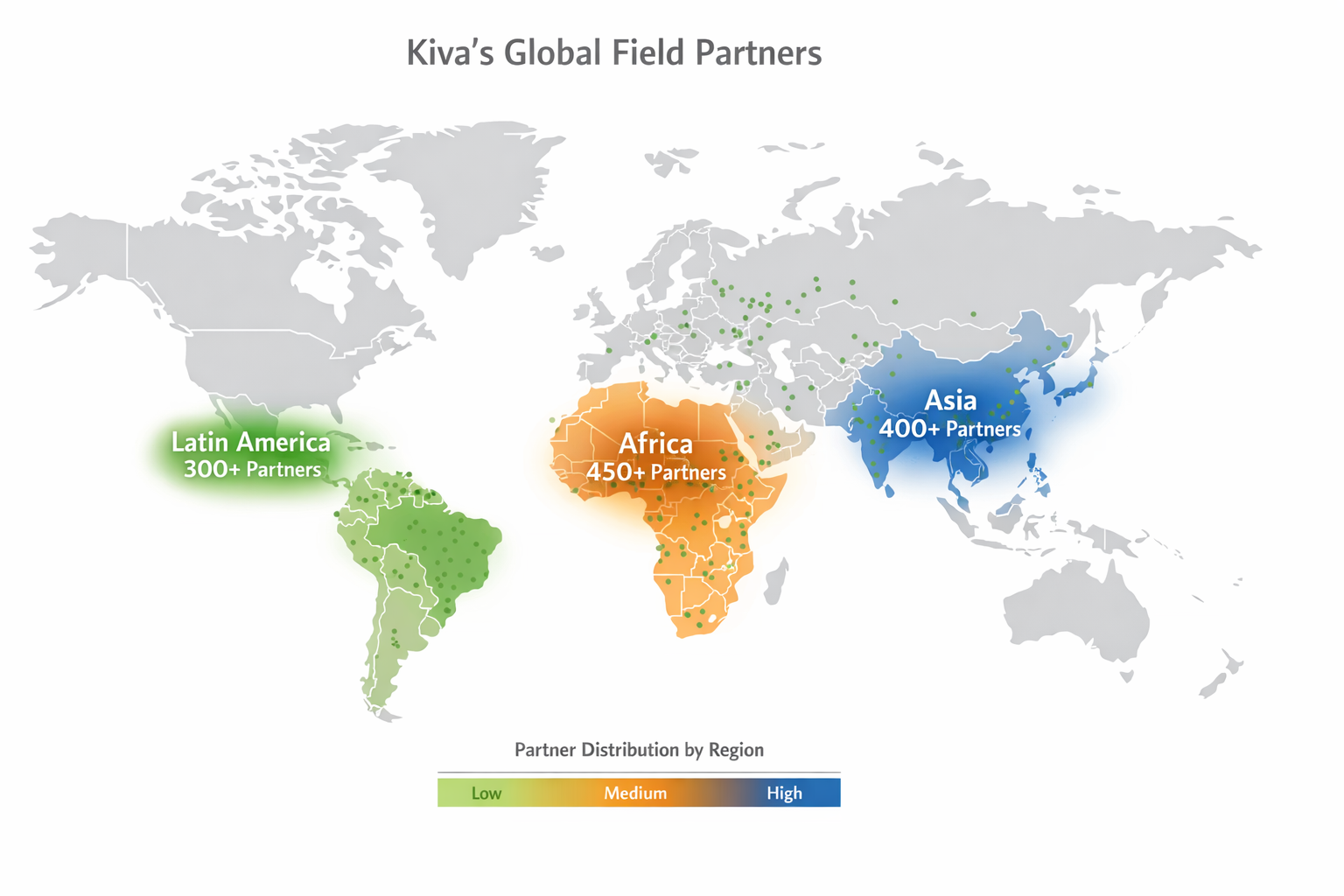

Kiva’s formative years were marked by rapid growth and increasing public recognition. By 2006–2007, Kiva had drawn media attention as an innovative blend of charity and fintech, and it quickly expanded its network of field partners (local microfinance institutions) to post loan requests from entrepreneurs in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and beyond.

A major boost came in 2009–2010, when high-profile figures highlighted Kiva’s work: Oprah Winfrey featured Kiva on her show as one of her “favorite things.

This exposure helped Kiva’s lender community grow exponentially.

By 2010, Kiva had facilitated over $100 million in loans, and that same year the Omidyar Network (founded by eBay’s Pierre Omidyar) awarded Kiva a $5 million grant to further develop its technology and reach.

Over the next several years, Kiva’s cumulative lending continued to accelerate: the platform reached $500 million in total loans by 2015 and then $1 billion by 2017.

Achieving the $1 billion milestone (representing 2.4 million borrowers funded by 1.6 million lenders at that point) solidified Kiva’s status as the world’s largest crowdfunding lender for underserved entrepreneurs.

Alongside growth in volume, Kiva diversified its program offerings. It launched new loan categories and partnerships: a Student Microloans program in 2010 to fund education, integration of “green loans” for clean energy and sustainable agriculture in 2011, and a focus on loans for women (who consistently received the majority of Kiva loans).

In 2011, Kiva also expanded domestically by piloting Kiva U.S. (initially called Kiva City and Kiva Zip), a program to crowdfund 0% interest loans for small business owners in the United States who lacked access to bank credit.

This was launched with support from President Clinton’s foundation and local community organizations, and eventually grew into a permanent Kiva U.S. program serving entrepreneurs in numerous cities (Detroit, New Orleans, Los Angeles, New York, etc.).

Changes in Leadership and Structure

As Kiva grew, its leadership and organizational structure also underwent transitions. The founding CEO, Matt Flannery, led Kiva for its first decade but stepped down in 2015 once the organization had over 100 staff and a maturing operation.

Premal Shah, a co-founder who had been Kiva’s President (and originally a former PayPal employee), continued to guide the company after Flannery’s departure.

Around this time, Kiva brought in experienced executives to manage its next stage: for example, Martin Tschopp (an eBay alumnus) briefly served as CEO in 2015 after Flannery.

By late 2017, Neville Crawley was appointed CEO, bringing a tech background to help scale Kiva’s platform. Under Crawley’s tenure (2017–2021), Kiva expanded its institutional partnerships and impact investments, but also navigated challenges like the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2021, Crawley departed and was succeeded by Chris Tsakalakis, a former StubHub president, as CEO. However, Tsakalakis served briefly – he resigned in mid-2022, citing personal considerations, after helping Kiva achieve a record year of lending in 2021.

Following his resignation, Kiva’s board chair (Julie Hanna) acted as interim leader while an executive search was conducted.

Throughout these changes, Kiva’s governance remained strong, with an active board that includes technology and finance leaders (e.g. Reid Hoffman of LinkedIn is a long-time board member).

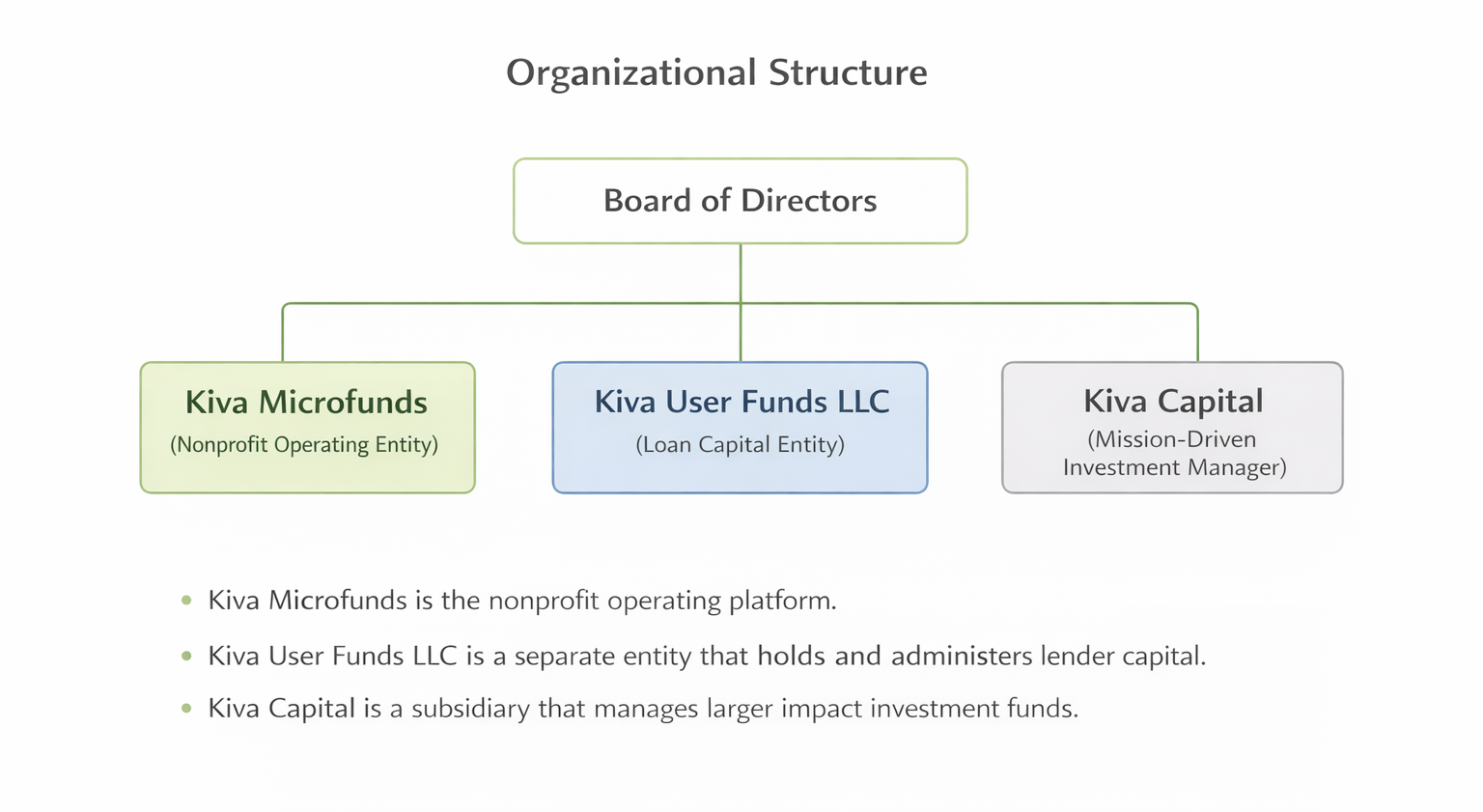

Kiva also adjusted its organizational structure to support its mission: it created separate legal entities like Kiva Microfunds (the 501c3 nonprofit), Kiva User Funds LLC (to hold lenders’ revolving loan funds securely), and Kiva DAF LLC (to manage donor-advised funds and institutional lending capital).

This structure ensured operational funds are segregated from loan capital, enhancing trust and financial oversight.

In summary, Kiva’s history can be seen in phases: a startup phase (2005–2009) establishing proof of concept, a rapid growth phase (2010–2015) scaling globally and diversifying programs (with key infusions of capital and celebrity endorsements), and a maturation phase (2016–present) marked by professional management, deeper partnerships, and investments in measuring impact.

Over time, Kiva stayed true to its original mission but also learned and adapted – for instance, incorporating feedback from lenders and the evolving microfinance field to refine its strategy (discussed later in Challenges and Lessons).

After 20 years, Kiva stands as a prominent case of a nonprofit blending Silicon Valley tech and humanitarian aims, with a rich history of innovation and impact.

Problem Definition and Social Context

The Core Problem – Financial Exclusion

Kiva was created to address a fundamental economic problem: the lack of access to affordable financial services for a huge population of low-income people, especially in developing countries.

Globally, an estimated 1.4 billion adults are “unbanked” – they have no access to basic banking, credit, or formal financial tools.

This exclusion is caused by multiple factors: poverty and irregular incomes, high fees or minimum balances that keep formal banking out of reach, lack of acceptable ID or collateral, and discrimination or social barriers (women, rural villagers, refugees, and other marginalized groups are often left out of traditional finance).

Without access to credit or savings, people have difficulty investing in businesses, education, or emergency needs, which perpetuates cycles of poverty.

Prior to the microfinance movement, the main options for the poor were often predatory lenders or informal borrowing at extortionate interest rates.

Even as microfinance institutions (MFIs) emerged from the 1970s onward – demonstrating that low-income borrowers, especially women, could be reliable borrowers – the demand far exceeded the supply of micro-loans.

By the mid-2000s, tens of millions of people had received microcredit, but hundreds of millions more remained unserved, and existing MFIs faced constraints in scaling up due to limited funding and high operational costs.

In summary, Kiva’s founders identified a two-fold problem: on the borrower side, small entrepreneurs needed loans of a few hundred dollars to improve their livelihoods but lacked options; on the capital side, everyday people who might be willing to help (beyond donating to charities) had no direct mechanism to lend money to someone in need in another country.

Who Is Affected

The problem of financial exclusion affects small entrepreneurs, farmers, and families in low-income communities worldwide, particularly in regions like sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and rural parts of Latin America.

These are often people running subsistence businesses – e.g. market vendors, seamstresses, livestock herders, smallholder farmers – or those needing funds for education or home improvements.

Kiva has especially focused on women borrowers, because women in many countries face additional barriers to credit (only 27% of women have access to formal financial services, vs 46% of men, according to data cited by Kiva).

Without access to loans or savings, these individuals struggle to expand their income-generating activities or buffer against shocks.

Prior solutions to support such people were either charity (donations or grants) or traditional microfinance via NGOs. Pure charity, while critical for emergencies, often isn’t sustainable or empowering long-term – beneficiaries don’t build credit history or business capacity, and donor funds are one-off.

Traditional microfinance NGOs, on the other hand, proved that loans could work for the poor but they were limited by how much capital they could raise from banks or donors and sometimes charged relatively high interest rates (often 20–40% annual) to cover their costs.

By the early 2000s, the microfinance sector was growing but also facing credibility tests (such as incidents of over-indebtedness and a crisis in India around 2010), indicating that fresh approaches were needed to reach more clients responsibly.

Scale and Urgency of the Issue

The sheer scale of the global “microfinance gap” provided urgency to Kiva’s mission. Even today, as noted, over a billion adults remain unbanked.

For context, the World Bank’s data showed that in the mid-2010s, only about 20% of adults in low-income countries had access to formal credit.

The mismatch between the small size of loans needed and the high cost of delivery has meant traditional banks stay away – it simply isn’t profitable for a bank to make a $100 loan to a rural villager.

This is where peer-to-peer lending via the internet appeared promising: it could unlock a new source of capital (individuals in wealthier countries) and bypass some costs by using technology.

The problem Kiva addresses is not just economic but deeply social: lack of credit can trap generations in poverty and exclude them from the modern economy.

Conversely, access to a modest loan can enable someone to buy a sewing machine, a dairy cow, or inventory – potentially yielding increased income, better nutrition, or money for children’s schooling.

Research has shown mixed but generally positive effects of microloans on such outcomes.

For instance, a comprehensive 2022 survey of 18,000 microfinance clients across 41 countries (the 60 Decibels Microfinance Index) found 88% of borrowers felt their quality of life improved and 73% reported higher household incomes after taking a micro-loan.

Such data underscores that while microfinance isn’t a silver bullet for poverty, it often provides a tangible boost in resilience and opportunity for the poor.

When Kiva was founded, there was also an untapped opportunity on the lender side: countless individuals were interested in helping with global poverty alleviation but wanted more direct, transparent connections to beneficiaries.

Traditional charities didn’t offer the feedback loop or personal engagement that a lending model could. Kiva’s emergence coincided with growing interest in “micro-philanthropy” and online platforms. The founders recognized that storytelling and person-to-person connection could galvanize ordinary people to become “bankers to the poor” in small increments.

In summary, the social context was a convergence of needs – borrowers needing capital, and socially conscious internet users looking for meaningful ways to make an impact – set against the backdrop of a microfinance movement seeking to scale up. Kiva’s solution sought to bridge these gaps, leveraging technology to channel resources to where they were most needed.

Program Model and Theory of Change

Kiva’s Core Program – Crowdfunded Microloans

Kiva’s primary program model is an online microlending platform that brings together individual lenders and underserved borrowers. The mechanics are as follows:

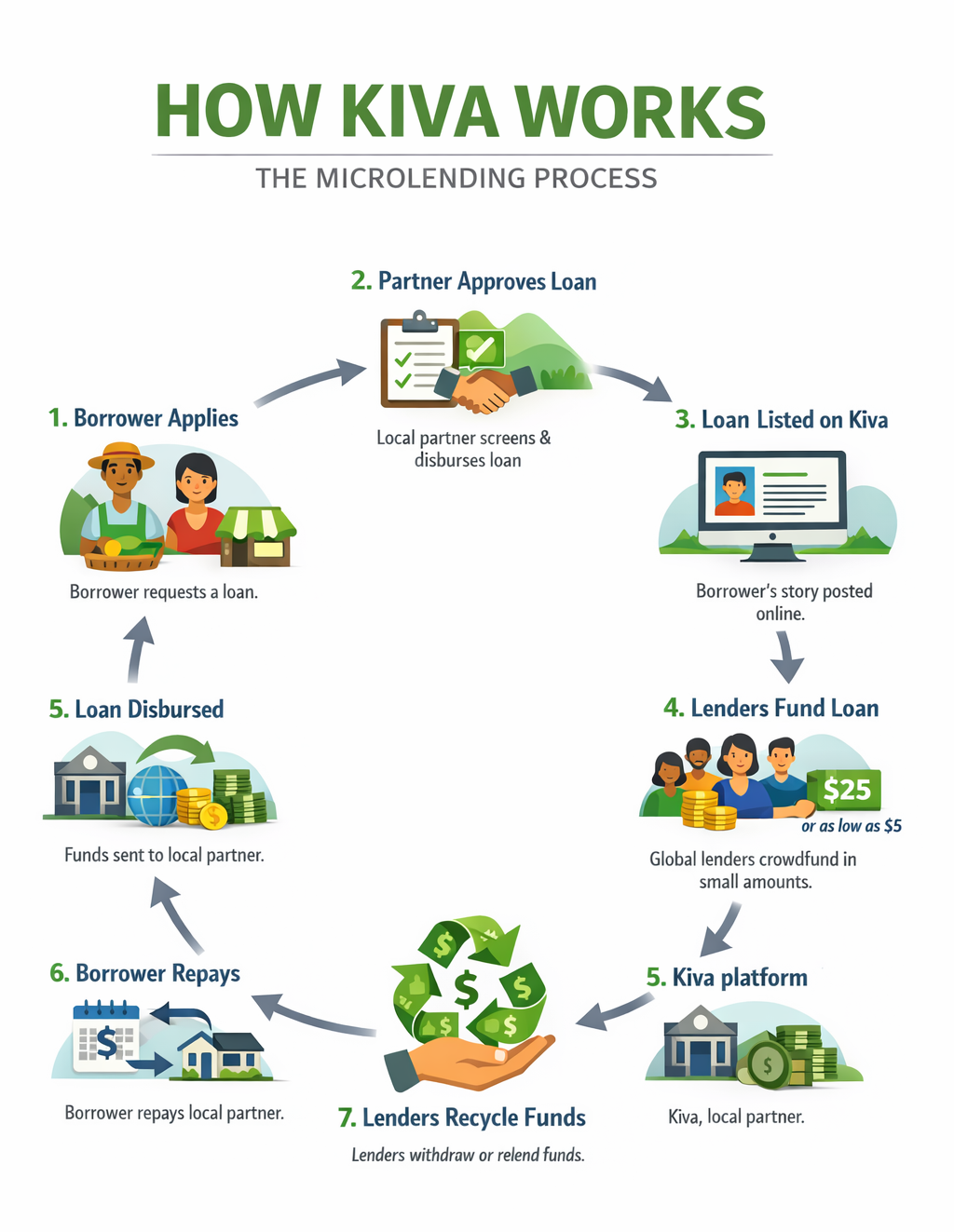

| Step | What Happens | Who Is Involved |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Loan application | A borrower applies for a loan to support a small business or economic need. | Borrower, local partner organization |

| 2. Screening and approval | The local partner evaluates the borrower for creditworthiness and social impact. If approved, the loan is disbursed before or shortly after being listed. | Microfinance institution, nonprofit, or social enterprise |

| 3. Loan listing | Kiva publishes the borrower profile with the story, purpose, and loan amount. | Kiva platform, borrower, partner |

| 4. Crowdfunding | Lenders fund the loan in small increments, typically $25 or $5 through monthly plans. | Global lenders |

| 5. Funding completion | Funds reimburse the partner or are transferred for disbursement once fully funded. | Kiva, local partner |

| 6. Repayment | Borrowers repay monthly to the partner, and repayments are credited to lenders. | Borrower, partner, Kiva |

| 7. Reuse of funds | Lenders withdraw or relend funds, allowing capital to be recycled. | Lenders |

A critical part of the model is Kiva’s network of Field Partners.

As of 2024, Kiva works with 285 active field partners in 96 countries, including microfinance institutions and other social enterprises.

These partners are responsible for identifying borrowers, administering and servicing the loans on the ground, and often providing additional support (like training) to borrowers.

Kiva performs rigorous due diligence on all partners and maintains quality standards – partners must have a social mission and fair practices (e.g. reasonable interest rates, no predatory tactics) to join the platform.

Kiva monitors partners’ performance and limits their borrowing capacity based on factors like repayment history. This partnership model extends Kiva’s reach globally without the need for Kiva to open branch offices everywhere.

It leverages the existing microfinance infrastructure while providing those institutions with a new, low-cost source of capital.

For borrowers in the United States, Kiva uses a slightly different direct lending model: borrowers apply online and, instead of a formal MFI, Kiva relies on a system of community-based trustees or a “social underwriting” process (the borrower must gather a small number of lenders from their own network first to vouch for them).

U.S. loans carry 0% interest and are managed directly by Kiva staff, since Kiva acts as the lender of record in these cases.

Theory of Change

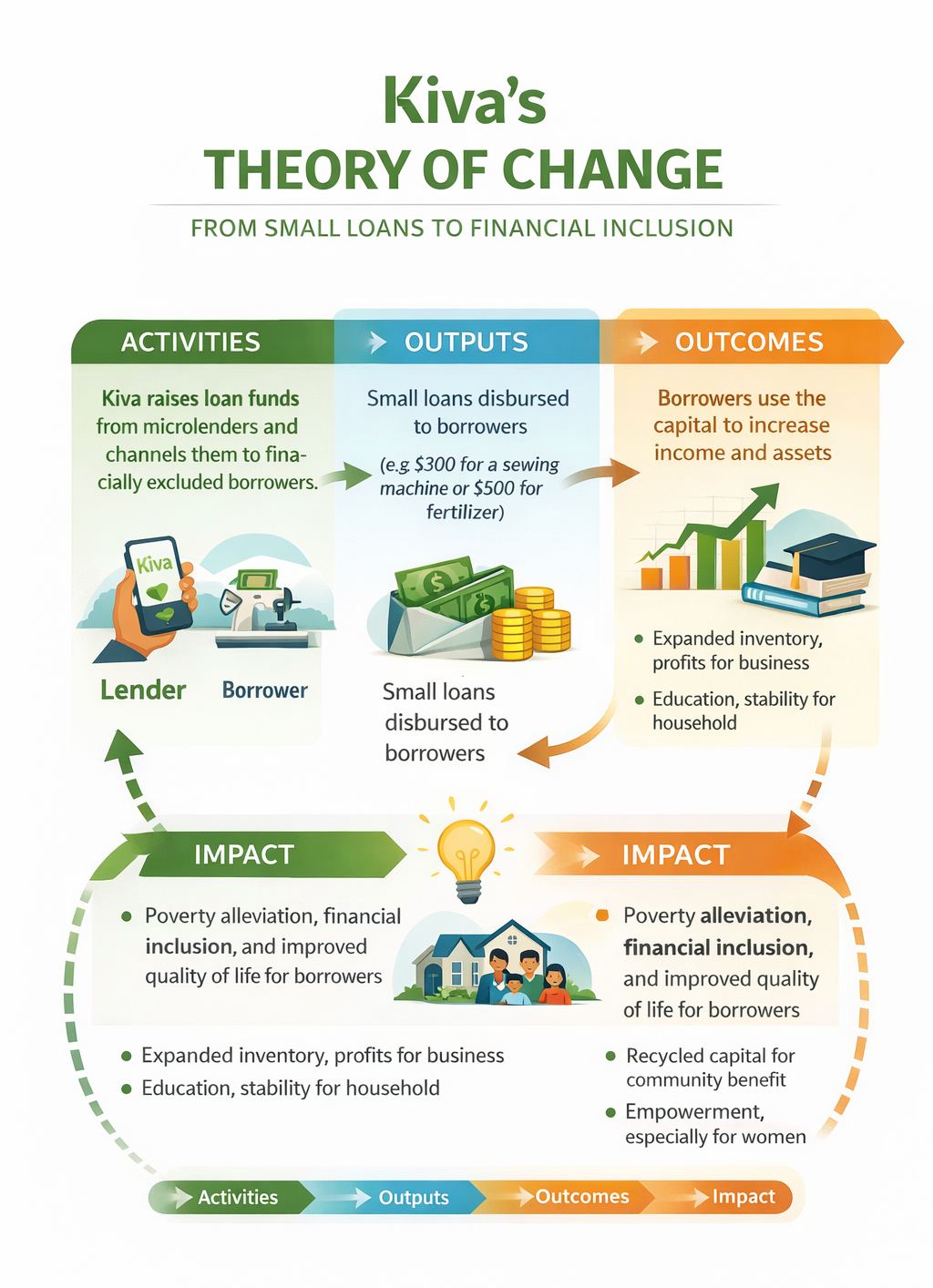

Kiva’s theory of change is rooted in the classic microfinance premise: Access to small amounts of capital can enable people to lift themselves out of poverty. The chain of logic is: Activities → Outputs → Outcomes → Impact.

At the activity level, Kiva raises loan funds from a broad base of microlenders and channels those funds to creditworthy but financially excluded borrowers. The immediate outputs are the loans disbursed – e.g., a $300 loan to a tailor to buy a new sewing machine, or a $500 loan to a farmer to purchase fertilizer.

The outcomes Kiva expects include the borrower using the capital to increase their income or assets (by investing in their business or education), which in turn leads to improved economic stability for their household. For instance, a borrower might be able to expand her inventory and see higher profits, or afford school fees for her children from the business revenue.

Over a longer term, the intended impact is poverty alleviation and improved quality of life: borrowers gain “financial inclusion” (a credit history, a relationship with a financial partner) and the capacity to improve their circumstances through their own initiative.

Kiva also posits a community and societal impact: as borrowers succeed and repay, the capital can be recycled to new borrowers, creating a multiplier effect. There is also an empowerment dimension – especially for women entrepreneurs who, with financial resources, may achieve greater agency and status in their communities.

Several assumptions underlie Kiva’s theory of change.

One is that lack of capital is a key constraint holding back many viable entrepreneurial efforts among the poor – if given a loan on reasonable terms, most borrowers will invest it wisely and be able to repay (evidenced by Kiva’s high overall repayment rate around 96%).

Another assumption is that even at 0% interest (to the lender) and modest interest to the borrower (often local MFIs charge interest to cover their costs), the model can be sustainable and not foster dependency.

In fact, repayment is integral: it instills a sense of accomplishment and responsibility in borrowers and lets the same funds help others in a continuous cycle.

Kiva also assumes that by vetting partners carefully and focusing on underserved client groups (women, rural, refugees, etc.), its loans will reach those who truly lack alternatives – rather than displacing other credit.

The model is supported by evidence from microfinance broadly, which shows that when designed well, small loans can lead to increased business investment, income smoothing, and greater resilience against shocks.

Kiva’s own impact surveys (in partnership with independent firm 60 Decibels) have provided data reinforcing these assumptions: e.g., large majorities of borrowers report using loans to grow businesses and being better able to handle unexpected expenses thanks to the financial access.

Program Variations and Complementary Initiatives

While the core model is microlending for micro-business, Kiva has extended its theory of change into related areas. For education loans, the idea is that a student can get a degree or vocational training thanks to a Kiva loan and thereby secure a better-paying job – breaking the cycle of poverty in the next generation.

For “Kiva Labs” pilots, the theory was that new approaches (like more flexible repayment schedules for farmers who have seasonal income, or special loan products for clean energy) could amplify impact by tailoring finance to borrower needs.

For example, Kiva has facilitated loans for solar lanterns and clean cookstoves; the outcome chain there includes both economic benefits (saving on fuel costs) and health/environmental benefits (less smoke inhalation, lower carbon footprint).

In high-risk contexts like refugee lending, Kiva’s theory of change includes the notion that providing capital to refugees (a group usually deemed “unbankable”) not only helps them rebuild livelihoods but also proves their creditworthiness, encouraging the formal sector to serve them in the future.

Kiva actually launched a World Refugee Fund and has shown that refugee borrowers repay on par with others (96% repayment, dispelling myths about their risk).

All these programmatic efforts tie back to Kiva’s central theory: when you “expand financial access”, individuals gain the power to improve their own lives.

Kiva stands in contrast to a charity model by emphasizing loans, not grants, thereby promoting a hand-up approach. To ensure this theory holds true, Kiva closely monitors whether borrowers succeed and repay without undue hardship.

It also invests in partner capacity (through initiatives like Kiva’s fellowship program sending skilled volunteers to assist partners, and offering partners tools and training).

The evidence gathered so far, both from repayment data and outcome surveys, suggests Kiva’s theory of change is valid in many cases: micro-borrowers typically utilize loans productively, and even modest income improvements can set in motion broader positive changes (better nutrition, education for children, etc.).

However, Kiva is cognizant of microfinance’s limitations: not every borrower will experience a dramatic business success, and some extremely poor or vulnerable individuals may need other forms of support before taking on debt.

Thus, implicit in the model is an understanding that microloans are one tool among many in development, best used for enterprising individuals with the capacity to invest the funds wisely.

Impact Measurement and Results

Measurement Approach

Kiva measures its success using a mix of output metrics, portfolio quality indicators, and, increasingly, social outcome evaluations.

Traditionally, Kiva tracked its reach and scale as primary metrics: total dollar volume of loans funded, number of loans, number of borrowers reached, and the breadth of countries and sectors.

These indicators speak to the immediate output of Kiva’s work.

For example, as of late 2025, Kiva’s all-time figures surpassed $2.4 billion disbursed in over 2.3 million loans, reaching about 5.6 million borrowers across 90+ countries.

Annual snapshots illustrate Kiva’s scale of operations: in 2021 alone, Kiva facilitated $223 million in loans for 556,000 borrowers in 65 countries – which equated to an average of $613,000 lent per day that year.

Even during the pandemic year 2020, Kiva’s community raised about $127 million in loans for roughly 170,000 borrowers, as Kiva focused on resilience lending during the crisis.

These output metrics are regularly published in Kiva’s annual reports and on its website, providing transparency to stakeholders. Kiva also monitors the composition of its impact – for instance, tracking the proportion of loans that go to women (historically around 80%), to rural borrowers (about 60% in recent years), or to high-impact categories like agriculture and education.

Another key performance indicator is repayment rate, which Kiva treats as both a measure of financial performance and a proxy for borrower success (a high repayment suggests the borrower’s venture generated enough income to pay back).

Kiva disaggregates this by loan type: partner-facilitated microloans (through MFIs) have about a 97.1% repayment rate, while the direct loans (e.g. Kiva U.S.) have a lower rate around 72.8%.

These numbers, updated periodically on Kiva’s “Due Diligence” page, allow Kiva to identify areas for improvement (for example, the much lower repayment on U.S. direct loans has prompted efforts to improve underwriting and borrower support in that program).

Another metric related to this is the currency loss rate (currently around 0.6%), which reflects foreign exchange losses that occur on some loans – a figure Kiva keeps low through careful financial arrangements.

Outcomes and Impact Data (Recent Years)

In the last 3–5 years, Kiva has significantly invested in measuring the social outcomes of its loans, not just the outputs. Partnering with independent evaluators and leveraging surveys, Kiva has gathered data directly from borrowers about how the loans affected their lives.

One major effort was contributing to the 2022 60 Decibels Microfinance Index, which surveyed clients of microfinance (including many Kiva borrowers via partners).

The findings provided strong evidence of positive change: 88% of borrowers said their quality of life improved since accessing loans, and 73% reported increased household income.

Borrowers cited reasons such as business growth, better ability to pay household expenses, and increased savings as ways the loan improved their lives.

Moreover, 70% of clients said having a loan helped them handle major expenses or shocks better (e.g. medical emergencies), indicating improved financial resilience.

These outcome statistics, drawn from tens of thousands of respondents, give Kiva a more nuanced picture of impact beyond just counting loans.

Kiva has also started reporting borrower self-reported outcomes on an ongoing basis. In its 2024 impact report, Kiva highlighted that nearly 90% of surveyed borrowers said their overall quality of life improved due to the loan, and about 8 in 10 increased their income (or felt more economically empowered).

Such high percentages are encouraging, though one should note that these are typically surveys of borrowers who completed a loan cycle, and there may be some survivor bias (borrowers who default or struggle might be less represented).

Still, Kiva’s use of third-party surveyors lends credibility to the findings, since borrowers may speak more freely to independent enumerators.

Kiva also tracks success stories qualitatively, through borrower stories and case studies, to illustrate impact.

For example, Kiva often shares profiles of borrowers who, with a loan, were able to start a new business or expand an existing one and subsequently hire employees or increase their family’s income.

These anecdotal successes align with the broader data trends.

In terms of scale of impact, Kiva reached a significant milestone in 2019 by directing over $1.3 billion to women since inception (by that point $1 billion of Kiva’s total lending had gone to women).

By 2025, the cumulative lending to women is around $1.5 billion benefiting 3.8 million women entrepreneurs, making Kiva one of the largest global platforms for women’s economic empowerment.

Kiva also measures impact in sectors: for instance, by 2017 it had funded over 19,000 “green” loans (for clean energy or eco-friendly projects) and over 4,500 loans to refugees.

By 2023, those numbers would be higher as Kiva deepened its work in these areas. All these contribute to broader outcomes like progress towards certain Sustainable Development Goals (no poverty, gender equality, etc.), which Kiva sometimes references in its reports.

Limitations and Shortfalls

Kiva is transparent that while most loans have positive outcomes, not all do. The roughly 3–4% of loans that default represent cases where borrowers could not repay, often due to reasons like business failure, personal hardship, or external shocks (droughts, conflicts, pandemics).

Additionally, some studies on microcredit (including a series of randomized controlled trials in different countries) have found that while microloans can increase business activity, they often have modest effects on long-term household consumption or poverty levels.

Kiva’s leadership acknowledges these debates and frames microloans as one tool among many for development, best combined with training, savings, and other services.

In practice, Kiva tries to amplify impact by working with partners that offer wraparound support (like vocational training or financial literacy) in addition to loans.

Another measured result is borrower satisfaction and protection.

The 60 Decibels survey indicated that 7 in 10 clients said their loan repayments were “not a problem” to meet and that they understood the loan terms well, suggesting that Kiva’s partners generally lend responsibly without over-burdening clients.

This is an important outcome: it speaks to client protection – loans are helpful, not harmful. However, the existence of the “Lenders on Strike” group (a cohort of Kiva lenders who became concerned that Kiva wasn’t as transparent about interest rates or was drifting from its mission) indicates that not all stakeholders were convinced by Kiva’s impact in recent times.

In 2021, some long-time lenders noticed Kiva’s site redesign made it harder to find the interest rate that field partners charge borrowers, which raised questions about transparency.

This controversy led to discussions about whether Kiva was emphasizing growth (and institutional partnerships) at the expense of its original spirit of direct connection and transparency.

Kiva responded by clarifying that interest rates and partner information were still available and by doubling down on impact measurement to show that borrowers were benefiting (the aforementioned research showing a definitive yes that microloans help).

In summary, Kiva’s impact can be summarized by the numbers of people reached (5+ million), capital mobilized ($2.4B+), and high repayment and borrower-reported benefits (around 80–90% positive outcomes).

Over the last few years, Kiva has demonstrated an ability to scale its reach (with 2021 being a peak year – over half a million borrowers funded in that year alone) and also provided evidence of meaningful outcomes like increased income and resilience.

It has also identified challenges such as lower performance in direct lending and the need to maintain transparency.

Going forward, Kiva’s impact measurement efforts are likely to continue focusing on client outcomes (via surveys) and portfolio quality, while perhaps exploring long-term community impacts (e.g. job creation by Kiva-funded businesses, education attainment for borrowers’ families) to fully capture the changes catalyzed by these microloans.

Funding Model and Financial Structure

Funding Sources

Kiva’s funding model is distinctive in that the loan funds and the operational funds are sourced separately. The loans that are lent out on the platform come from crowd lenders and are not a revenue source for Kiva – those funds circulate in and out to borrowers.

To finance its operations (staff salaries, technology infrastructure, partner monitoring, etc.), Kiva relies on a combination of donations, grants, and fees that make up its annual revenue.

The single biggest source is voluntary donations from Kiva’s own lenders at the point of transaction.

Whenever a lender makes a loan on Kiva.org, they are prompted with an option to add a tip (typically 15% of their loan or a custom amount) as a donation to Kiva.

According to Kiva, these user donations cover more than two-thirds of Kiva’s operating costs. This is a clever model because it harnesses the “power of the crowd” not just for loans but also for sustaining the platform itself, and it keeps traditional fundraising costs lower.

The remainder of Kiva’s funding comes from philanthropic grants and corporate/foundation support, as well as a relatively small amount from earned revenue.

On the philanthropic side, Kiva has attracted major grants over the years. For instance, in its early growth, the Omidyar Network’s $5 million grant (2010) and the Skoll Foundation’s $1 million grant (2007) were pivotal.

Other foundations like Ford Foundation, Google.org (through the Google Global Impact Award of $3M for Kiva Labs), and more recently, funders focusing on refugees or climate, have contributed restricted and unrestricted funds.

Some high-net-worth donors and tech philanthropists have also backed Kiva due to its Silicon Valley ties. On the corporate side, Kiva has formed partnerships where companies provide sponsorship or in-kind support.

The most notable is PayPal, which not only processed transactions for free (effectively a subsidy worth millions in saved fees), but also partnered in campaigns and events. Companies like Pepsi, HP, and others have done matching loan campaigns or encouraged employees to lend on Kiva, sometimes also donating to Kiva’s operations as part of CSR initiatives.

In terms of earned revenue, Kiva historically charged no fees to lenders or borrowers for using its platform. However, in recent years it introduced some service fees to certain Field Partners. Specifically, “a select number” of larger lending partners pay a fee for use of the platform and Kiva’s services.

This is a relatively new development aimed at enhancing sustainability – for example, a microfinance institution that raises a significant amount of capital via Kiva might pay a small percentage fee to Kiva.

These fees remain a minor part of the revenue mix (Kiva says partner service fees are one of the smallest portions, after lender donations and grants).

Additionally, Kiva earns some investment income on the float of funds. Kiva holds lenders’ funds (when they are not deployed in loans or when repayments are waiting to be withdrawn or reloaned) in secure accounts or treasuries via a wholly owned entity (Kiva User Funds LLC).

The interest from these holdings can be used for operations. In FY2024, for example, Kiva’s financial statements show over $5 million in investment and interest income, reflecting interest gains from lender funds (especially as interest rates rose in 2022–2023).

Financial Structure and Budget

Kiva Microfunds, the nonprofit entity, has an annual operating budget in the tens of millions. In the recent fiscal year, Kiva’s total revenue was about $34.3 million, against total expenses of about $35.4 million.

The revenue composition included roughly $27.7M in contributions and grants (which encompasses those lender tips and external donations), about $1.0M in program service revenue (likely partner fees or similar), ~$5.0M in investment income, and a small amount of other income.

This mix demonstrates Kiva’s heavy reliance on contributed income versus earned income – appropriate for a nonprofit, but it also means Kiva must maintain a strong fundraising program and appeal to its community’s generosity continually.

One notable aspect is that Kiva’s lender base itself has become a massive fundraising engine: as mentioned, over two-thirds of costs are covered by lender donations at checkout.

This suggests that Kiva’s millions of lending transactions each year effectively crowdsource the operational budget in small increments. It’s a decentralized funding model akin to Wikipedia’s user donation model, creating a broad base of support and reducing dependency on any single donor.

Kiva’s policy of “100% of loans to borrowers” (meaning it does not take a cut from the loan principal or charge interest to the lenders) is a cornerstone of its model.

This is appealing to users but also necessitates the dual revenue approach described. By segregating Kiva User Funds LLC (which holds all lender funds) from Kiva Microfunds (which spends donations on ops), Kiva ensures clarity that no operational shortfall will be covered by dipping into loan capital.

This separation also legally protects lender money if Kiva were ever in financial trouble, as those funds aren’t considered Kiva’s assets but are held for the lenders’ benefit.

Financial Sustainability and Risks

Kiva has generally managed to balance its budget or run small deficits covered by reserves. The FY2024 figures show a slight deficit (~$1.14M), following a larger deficit the prior year (~$2.9M).

These shortfalls were likely planned as Kiva invested in growth and weathered the pandemic. Kiva still had nearly $30M in net assets in mid-2024 to cushion any gaps.

A key to sustainability is keeping a diversified funding base. Kiva’s reliance on small lender donations is a strength (broad base) but also a risk if lender activity declines. For example, if loan volumes drop or if fewer lenders add a tip, Kiva’s largest income stream could fall.

To mitigate that, Kiva continues cultivating major donors, and it introduced the partner service fees to slightly diversify income. It also runs occasional fundraising campaigns and asks high-capacity lenders to become patrons or monthly donors.

Another risk is funding concentration: a large portion of Kiva’s donations might actually come from a relatively small percentage of very active lenders.

Kiva doesn’t publicly break down how much of the ~$27M in contributions is from $2 tips versus big grants, but one can infer that some significant grants (like multi-million from foundations) are included there.

The loss of a major grant or a downturn in user donations could necessitate cost-cutting or drawing on reserves.

Operationally, Kiva maintains lean efficiency partly by leveraging volunteers and interns (who were unpaid for much of Kiva’s history, though they began paying interns in 2019).

Volunteer translators/editors allow Kiva to process loan postings in many languages daily without proportional cost increase.

This in-kind support is a sort of hidden funding – in 2023, Kiva listed 526 active volunteers contributing their labor, which bolsters its capacity.

In summary, Kiva’s financial structure is a blend of crowdfunding and traditional fundraising. It has proven to be relatively robust, as evidenced by the organization sustaining and growing for 20 years without charging platform fees to users.

The commitment to pass 100% of loan funds to borrowers necessitates continual fundraising creativity. So far, Kiva has shown that the crowd can indeed fund the engine that powers the crowd’s loans – a virtuous cycle of lender involvement.

Financially, Kiva operates much like a tech-enabled nonprofit, with significant upfront investment in platform and partnerships, then relying on volume to generate the donation flow to cover costs.

Its main ongoing tasks in funding are to keep lender engagement high (so tips flow), retain the confidence of major donors, and carefully manage expenses to not outstrip revenue.

Given its track record and the relatively predictable nature of a large lender base, Kiva’s funding model has been largely successful, though it will need to adapt if any one stream (like user donations) faces headwinds.

Financial Performance and Stewardship

Budget Size and Growth

Kiva’s financial statements reflect a mid-sized nonprofit with a budget that has grown in line with its program scale. In recent years, annual expenses have been on the order of $30–35 million.

This finances a global operation (with ~150 staff) and the technology infrastructure for a platform handling hundreds of millions in transactions per year.

Kiva’s financial trajectory shows an initial period of very rapid budget growth in the late 2000s (as it moved from a startup to an organization handling tens of millions in loans), followed by more moderate growth and some plateauing in the late 2010s.

For instance, Kiva’s Form 990 from 2012 showed ~$15M in expenses, whereas a decade later it’s about double that, indicating steady expansion but not exorbitant growth.

The pandemic in 2020–2021 saw a spike in activity (and costs to match) – in 2021, Kiva’s expenses jumped as it processed a record volume of loans ($223M), but those were mission expenses directly tied to helping 550k entrepreneurs through the crisis.

Program vs Administrative vs Fundraising Expenses

Kiva is highly program-focused in its spending, as one would hope for a nonprofit. Charity Navigator reports Kiva’s program expense ratio as about 76.7%, meaning roughly three-quarters of expenditures go directly to program services (maintaining the lending platform, supporting field partners, loan processing, etc.).

The remaining quarter is split between administrative and fundraising. Kiva’s ratio earned it a maximum score on Charity Navigator’s rating for financial health.

Looking at Kiva’s FY2024 Form 990 summary, out of ~$35.4M total expenses, about $27.5M were program service expenses.

Management and general plus fundraising likely made up around $7.9M combined. Kiva’s fundraising expenses are relatively low (in the 5–10% of budget range) because it does not rely heavily on costly fundraising events or mass marketing – the built-in donation-at-checkout mechanism is very cost-efficient (essentially no extra cost to raise those funds).

Administrative costs include running the website, compliance (since moving money globally is complex), staff management, and similar overhead.

Kiva leverages a lot of volunteer effort (e.g. the Kiva Fellows program, which places volunteers at partner sites, and online loan reviewers) to extend its program reach without proportional cost, which helps keep the program efficiency ratio high.

Allocation of Funds

The bulk of Kiva’s spending goes toward maintaining and growing the lending platform and supporting its field operations network. Concretely, major expense categories include: Salaries and Personnel – at nearly $18 million in FY2024, salaries and benefits for staff are the single largest expense.

Kiva’s team includes software engineers, product managers, partner relationship managers, impact and evaluation staff, marketing/outreach, and support teams. This investment in human capital reflects that Kiva is essentially a service delivery and tech organization.

Another significant expense area is Technology and Infrastructure – keeping the Kiva website and transaction systems running securely 24/7, developing new features (like the mobile app or new funding products), and data security measures.

While detailed breakdown isn’t publicly itemized, these would fall under program services because the platform is the program.

Kiva also incurs costs in Field Partner support and oversight: conducting due diligence visits, audits, training for partners, and monitoring. Kiva historically sent dozens of volunteer Kiva Fellows each year (stipends or minimal cost) to assist partners, but staff also travel for partner management and to launch initiatives (though travel was curtailed during COVID).

Additionally, Kiva sometimes grants out funds or invests in pilot projects – for example, in 2020, Kiva issued “Crisis Support Loans” to help 36 partner MFIs with liquidity during the pandemic (total $7.2M).

These were essentially loans to partners rather than through partners, and might be recorded differently in financials. Kiva doesn’t typically make grants to others (aside from passing lenders’ loan funds), but in the Form 990 we see a small entry of $126k in grants in FY2024, possibly a one-time community initiative or leftover DAF distribution.

Use of Funds Across Programs

Kiva’s spending supports multiple program areas: the international lending program, the U.S. lending program, strategic initiatives like Kiva Labs and Kiva Capital, and the newer Kiva Protocol (until it wound down).

However, these are not separate silos; mostly they share infrastructure.

For instance, Kiva U.S. loans are funded on the same platform as other loans, but require some dedicated staff for borrower onboarding in the U.S. The Form 990 Part III indicates Kiva’s top three program services by expense.

The text from FY2024 990 notes that “Kiva partners with 285 global MFIs... enabling Kiva to connect with borrowers... Kiva’s partner organizations are responsible for vetting and administering loans” and that the online platform connects these borrowers with over 2.22 million lenders.

This description, tied to an expense number, likely corresponds to the main international program costs (which could be on the order of $20+ million). It also mentions “Kiva facilitates direct loans to individuals in the United States”, which would be the second program listed, though the expense allocation for that is smaller (Kiva US is a subset of total loans – e.g., $7.8M lent in the U.S. in 2020 vs tens of millions in other regions).

So maybe a few million dollars of expenses go to running the U.S. program. The third program could be something like Kiva DAF/Capital or technology development, but the 990 excerpt is cut off. In any case, Kiva ensures donations are tracked and used to support these programmatic goals, and if a donation is restricted (say, a grant for refugee loans or for building Kiva Protocol), it is spent accordingly.

Partnerships and Ecosystem

Field Partner Network

Kiva’s most important partners are its Field Partners, microfinance institutions, cooperatives, NGOs, and social enterprises that originate and manage loans on the ground. With 285+ active partners across 90+ countries, Kiva depends on these organizations to identify borrowers, vet applications, post loans to Kiva’s platform, disburse funds, and collect repayments.

In return, partners gain access to 0% interest capital and visibility to new funding sources. This structure is practical. Kiva cannot operate at global scale without local institutions, and partners can expand lending capacity and reach borrowers they might otherwise avoid.

Partner Selection and Management

Kiva runs a structured due diligence process that reviews partner mission alignment, financial stability, portfolio quality, borrower pricing, and client protection practices. Partners receive internal risk ratings and trust tiers that influence how much they can raise on the platform.

Kiva monitors partners over time because partner performance directly affects repayment outcomes and lender confidence. When partners fail or violate standards, Kiva has suspended or ended relationships in the past.

To reduce concentration risk, Kiva limits portfolio exposure so no single country or partner dominates, spreading risk across a broad set of geographies and institutions.

Key Institutional Partners and Alliances

Kiva also works with corporations, foundations, and public sector entities to extend reach and reduce operating friction.

Corporations and businesses have supported Kiva through payment processing, marketing partnerships, and matching programs that encourage lenders to fund specific themes or communities.

Foundations and philanthropic collaborators have provided large grants and strategic support, helping Kiva test new initiatives and expand its ecosystem credibility.

Government and multilateral partners have engaged with Kiva through targeted programs and pilots, especially when public agencies want a channel to deliver 0% capital to small businesses or underserved groups.

Value and Support from Partnerships

Partnerships provide three concrete advantages.

- Distribution and scaleBrings in new lenders and additional capital, increasing funding volume and reach.

- Operational leverageLowers or offsets operating costs, for example transaction processing, and helps fund targeted initiatives.

- Local executionEnables on the ground delivery, including borrower screening, loan disbursement, repayment collection, and often training or business support that can improve outcomes.

This typically complements traditional microfinance funding, since 0% capital can lower a partner’s cost of funds and expand lending to higher risk or underserved borrowers.

Operations and Organizational Capacity

Staffing and Human Resources

Kiva operates with a lean professional staff of roughly 140–150 full-time employees globally. Headquarters are in San Francisco, with regional hubs in Nairobi and Bangkok supporting partner relationships in Africa and Asia, and a smaller presence in Portland, Oregon for product and support functions.

Staff roles span engineering, product, finance, risk, partner management, impact, and communications, with a strong emphasis on technology given Kiva’s platform-based model.

Kiva’s paid staff is significantly augmented by volunteers. Hundreds of volunteers support the Review and Translation Program, enabling loan profiles to be published quickly and at low cost.

The Kiva Fellows Program places skilled volunteers with field partners for short-term assignments, strengthening reporting, training, and partner capacity. This volunteer infrastructure allows Kiva to operate at global scale without proportional staff growth.

Governance Structure

Kiva is overseen by an active Board of Directors composed of leaders from technology, finance, and the social sector. The board is closely involved in strategy, financial oversight, and executive leadership transitions, including stepping in during interim CEO periods.

An executive leadership team manages day-to-day operations, supported by audit and governance committees that provide accountability.

CEO History at Kiva

| CEO (full name) | Date served |

|---|---|

| Matt Flannery | 2005 to 2015 |

| Neville Crawley | 2017 to 2021 |

| Chris Tsakalakis | 2021 to July 22, 2022 |

| Julie Hanna (Interim) | July 22, 2022 to 2023 |

| Vishal Ghotge | 2023 to Present |

Operational Processes

Core operations center on managing loan origination, funding, repayment, and reporting across more than 70 countries.

Kiva coordinates payment flows with banks and processors, manages foreign exchange and regulatory compliance, and monitors partner performance through a dedicated risk and compliance function. Loan posting and repayment is a continuous, global process requiring coordination across time zones.

Customer support focuses primarily on lenders, handled through an online help center and a small support team. Borrower support is delivered indirectly through field partners.

Technology and Platform

Kiva’s operational capacity is tightly linked to its technology. The platform supports millions of users, high transaction volumes, and public transparency into loans and partner performance.

It includes tools for loan discovery, team lending, repayments, and APIs for integration. Kiva uses cloud infrastructure for scalability and invests continuously in security and reliability. Periodic platform redesigns have modernized the system, though not without tradeoffs for long-time users.

Challenges and Constraints

Funding Volatility and Sustainability

Kiva’s operating model depends heavily on voluntary lender donations, which creates revenue volatility tied to lending volume and donor sentiment. This has been a recurring challenge during periods of rapid growth and crisis response.

During the 2008–2009 financial crisis and again during the COVID-19 pandemic, Kiva experienced surges in lending activity that required rapid operational scaling. In 2020–2021, Kiva ran operating deficits as it expanded crisis response programs and absorbed higher credit stress.

Leadership chose to draw on reserves and intensify fundraising, securing emergency grants and mobilizing its lender community to stabilize operations.

A related challenge is donor understanding. Kiva’s model is sometimes misunderstood, with some users assuming borrower interest payments fund Kiva’s operations.

Periodic community pushback, including concerns about institutional capital and perceived corporatization, has required Kiva to reinforce transparency and reaffirm its commitment to the crowd lending model.

Regulatory and Compliance Barriers

Operating across dozens of jurisdictions exposes Kiva to complex regulatory requirements governing foreign capital, crowdfunding, and money movement. Restrictions in large markets such as India have constrained growth at times, while currency controls and sanctions regimes in certain countries have required careful risk management.

Kiva has introduced mechanisms such as optional currency risk sharing for lenders and conducts extensive compliance checks to meet U.S. and international regulations. These constraints increase operating complexity and limit flexibility in certain regions.

Partner and Portfolio Risk

Kiva has faced periodic partner failures, fraud cases, and governance concerns among field partners. High-profile incidents, such as the suspension of a major Nigerian partner over transparency and pricing issues, prompted tighter due diligence and greater public disclosure.

Economic downturns and the COVID-19 pandemic also led to delayed repayments and restructurings. While lenders generally bear loan losses, Kiva has mitigated risk through diversification, loan loss reserves, and transparent communication. Overall repayment performance has remained strong, but partner risk remains an inherent constraint of the model.

Leadership Transitions

Kiva experienced multiple CEO transitions over a relatively short period, creating potential instability in strategy and internal alignment. Board intervention, including interim leadership, helped maintain continuity, but leadership turnover likely caused temporary disruption and organizational strain.

Maintaining momentum through transitions has required strong departmental leadership and active governance.

Technology and Market Pressures

As a digital platform, Kiva must continuously invest in technology modernization to meet user expectations and handle scale. Platform redesigns and feature changes have occasionally alienated long-time users, highlighting the tension between modern user experience and transparency for power users.

At the same time, competition in the social finance and fintech space has increased, while borrowers now have more alternatives through mobile lending and digital credit products. Kiva has responded by focusing on underserved segments and strengthening partner capabilities.

Program Pivots and Strategic Discipline

Not all Kiva initiatives have succeeded.

Programs such as Kiva Zip and Kiva Protocol demonstrated innovation but also revealed limits around repayment performance, operational cost, and scalability.

In both cases, Kiva chose to integrate or wind down efforts rather than continue unsustainable models. These decisions reflected a willingness to prioritize mission effectiveness over sunk costs.

External Shocks and Structural Tensions

Political instability, conflict, natural disasters, and global economic cycles regularly affect Kiva’s portfolio and partners. These shocks test repayment performance and require flexibility in loan terms.

More broadly, Kiva must continuously balance the needs of two core constituencies: lenders who demand transparency and engagement, and borrowers who need flexible, affordable capital delivered through partners. Aligning both sides remains an ongoing operational challenge.

Key Lessons and Takeaways

Kiva’s two-decade journey provides a rich case study for other nonprofit and social enterprise leaders. Here are several concrete lessons drawn from its experience, grounded in data and specific outcomes:

1. Leverage Technology and Storytelling to Mobilize the Crowd

Kiva demonstrated that a well-designed online platform, combined with compelling personal stories, can unlock unprecedented funding for social causes.

Early on, Kiva’s founders tapped into people’s desire for connection – they put faces and narratives to microloan applicants, which converted abstract poverty statistics into relatable human stories.

This storytelling was “a revolutionary change in the world of global financial inclusion,” as President Clinton noted.

The result: millions of everyday individuals became micro-lenders, contributing over $2.4B to borrowers who previously had no access to capital.

The lesson for others is to harness technology not just for efficiency but for human connection. Kiva kept its web interface simple and user-centric, allowing even a $25 lender to feel like a part of someone’s success story.

By sharing field updates and borrower progress, Kiva sustains engagement. For nonprofits, this underscores the importance of investing in digital tools and authentic narratives.

Especially in sectors where trust and tangibility are barriers (like lending money overseas), technology paired with transparency can bridge the gap.

Kiva’s success also shows the power of virality: a mention on Oprah or social media can exponentially increase reach, but that only translates to action if an easy-to-use platform is in place.

Thus, organizations should focus on building accessible digital channels and telling stories that resonate to galvanize public support at scale.

2. Innovate the Funding Model – Don’t Fear Unconventional Approaches:

One of Kiva’s bold innovations was its decision to run a loan program where lenders earn no interest and the nonprofit itself takes no cut from loans. This was a radical departure from traditional financial or charity models.

To make it viable, Kiva pioneered a tip-based revenue model, essentially crowdsourcing its own overhead. Over two-thirds of Kiva’s budget now comes from voluntary tips by users.

Many experts might have doubted that people would donate extra on top of lending, but Kiva proved that if users believe in a mission, they will support the platform enabling it – in 2021, for example, over 480,000 lenders and supporters collectively contributed to Kiva’s milestone year.

The key lesson: financial sustainability can be achieved in mission-aligned ways. Rather than charging borrowers (which could undermine their mission of affordable credit) or charging lenders a fee (which might deter participation), Kiva found a third way by inviting donations.

This model kept Kiva’s incentives aligned with impact – 100% of loans go to borrowers – while still covering costs through community generosity. Other nonprofits can learn from this to think outside the box in revenue streams.

Whether it’s a “pay what you want” model, freemium services subsidizing free users, or cross-subsidies, being creative and mission-focused in funding can maintain trust and long-term viability.

Kiva’s approach, backed by data, worked: it consistently raises ~$30M+ annually in contributions and grants, fueling its programs without resorting to fees that conflict with its ethos.

3. The Importance of Transparency and Accountability to Stakeholders

Kiva’s journey was not without controversy – at times it faced criticism from its own community (e.g., over interest rates and how loans are disbursed). The way Kiva handled these issues is instructive.

When it came to light around 2009 that many Kiva loans were actually pre-disbursed by partners (meaning lenders were technically refinancing existing loans), some users felt misled.

Kiva responded by immediately updating its FAQs and website language to clearly explain the process, reinforcing transparency.

It did not hide the fact; instead, Kiva’s leadership engaged in dialogue (even replying to critiques on forums like NextBillion) and reaffirmed their commitment to honesty. Likewise, for interest rates: Kiva now publishes each partner’s average interest rate and fee to borrowers, and it contextualizes why they might be high (e.g., the costs in rural lending) rather than leaving lenders in the dark.

The lesson is that transparency builds trust, even when the truth is complex. Rather than fearing that donors “can’t handle the truth,” Kiva treated its lenders as partners who deserved full information.

This has paid off: Kiva maintains a Platinum transparency rating and strong loyalty among lenders. Moreover, Kiva instituted more rigorous due diligence and public reporting (via its “Due Diligence” page showing repayment stats, currency loss, etc.) to hold itself accountable.

In practice, this means other organizations should proactively share both successes and shortcomings with stakeholders. Admitting a program limitation or a challenge (like Kiva did with the lower repayment of direct U.S. loans at ~73%) may invite scrutiny, but it also invites solutions and maintains credibility.

Kiva’s experience shows that users appreciate candor and will continue to support a mission if they trust the organization’s integrity.

4. Strong Partnerships and Local Engagement are Key to Scalable Impact

Kiva’s model underscores that to effect change on a global scale, you must work through strong local partners and community networks.

Kiva’s partnership with 285+ microfinance institutions in 96 countries was the engine behind reaching over 5 million borrowers.

These partners brought local expertise – they know how to lend in their communities, assess clients, and provide support services. Kiva’s role was to select, vet, and empower these partners with capital and technology.

The result was a high repayment rate (~97% on partner loans) and the ability to penetrate areas that Kiva staff themselves could never reach.

The takeaway is twofold: choose partners carefully and invest in them, and respect local knowledge. Kiva didn’t try to build its own field offices everywhere or micromanage how loans are used; it set standards (e.g., no predatory practices) and then trusted partners to implement.

When issues arose, like a partner running into trouble, Kiva addressed it jointly (sometimes even offering crisis support loans to help an MFI through tough times, as in 2020).

This collaborative approach meant Kiva could scale relatively quickly – by 2013, Kiva had a presence in over 70 countries, far more than it could have managed with a wholly-owned operation.

For other nonprofits, the lesson is to map the ecosystem and find allies – whether they are local NGOs, government agencies, or community groups – and build capacity together.

It often yields more sustainable outcomes.

Also, maintaining open communication and alignment with partners is crucial; Kiva ensured mission alignment by partnering exclusively with institutions committed to serving the poor or excluded.

This alignment prevented mission drift and meant Kiva’s growth amplified its mission rather than diluting it.

5. Focus on Mission Impact and Adapt Based on Evidence

Kiva’s trajectory shows a commitment to learning what works and pivoting when something doesn’t.

For example, early microfinance rhetoric claimed massive poverty reduction, but studies later showed more modest impacts. Kiva did not ignore this; instead, it delved into measuring its own impact.

By 2022, Kiva and its peers commissioned the first Microfinance Social Performance Index and found clear evidence of positive outcomes (88% reporting improved quality of life, etc.).

This evidence affirmed that Kiva’s approach – especially focusing on women and first-time borrowers (over half of those surveyed were first-time borrowers through an MFI) – was making a difference in ways that matter to clients.

At the same time, Kiva recognized not all models yield equal results: its direct peer-to-peer pilot in the U.S. had a lower repayment and likely higher default stress for borrowers, so Kiva integrated the best elements of that program (direct lending in the U.S. with trustees) into the main platform but dropped aspects that weren’t sustainable (like a standalone separate site).

The lesson here is be mission-driven, not model-driven. Kiva’s mission is financial access, not a specific means of delivery.

So it wasn’t wed to one approach; it evolved – adding student loans in 2010 when evidence showed education loans can be transformative, or launching green loans when it saw a need for energy access finance.

When something didn’t work as hoped (Kiva Protocol’s closure, for instance), it made the tough decision to redirect resources.

Organizations should similarly institute feedback loops: gather data, solicit stakeholder feedback, and be willing to pivot or refine programs to maximize impact. Kiva’s ability to hit a 96% overall repayment while reaching very risky populations (refugees, etc.) suggests it fine-tuned its methods (e.g., requiring trustees for U.S. loans to improve accountability).

The commitment to client protection – evidenced by Kiva only partnering with those who adhere to fair lending norms – further highlights keeping mission (helping, not harming, the poor) at the forefront.

In essence, relentlessly pursue the mission goals, but remain flexible on the methods, guided by data and client voices.

6. Cultivate Community and Trust for Long-Term Resilience

A subtler but powerful lesson from Kiva is how it built a community ethos among its lenders, volunteers, and borrowers, which became a source of resilience.

Kiva’s lenders often describe themselves not just as users of a platform but as part of the “Kiva community.” This is a result of deliberate efforts like Kiva lending teams, regular communication highlighting lenders’ collective impact, and even incorporating user feedback into decisions.

For example, when lenders raised concerns about changes in the website, Kiva’s CEO and board engaged and took that feedback seriously.

This inclusive approach fostered a sense of co-ownership. As a result, during tough times (like the pandemic), Kiva could rally its community to step up, and they did – 2020 saw lenders rapidly fund loans for struggling businesses, and 2021 was Kiva’s biggest year ever.

Volunteers, too, are deeply loyal: many Kiva editors/translators have contributed for years, effectively becoming goodwill ambassadors.

The takeaway is that beyond transactions, building a movement or community around your mission can greatly enhance stability and impact. Trust is the currency in this community – Kiva earned it through transparency and results, and in turn the community sustained Kiva.

For nonprofits, this means treating donors and beneficiaries as partners in the mission, keeping them informed and engaged beyond just asking for money, and providing avenues for deeper involvement (volunteering, advocacy, feedback loops).

Kiva’s story shows that when people feel part of something larger – “a collective movement made up of everyday heroes,” as a Kiva team member put it – they will stick with you and even amplify your mission.

In summary, Kiva’s experience teaches that innovation, integrity, collaboration, adaptability, and community-building are critical ingredients for nonprofit success.

By embracing these lessons – using technology to connect hearts and wallets, designing funding models aligned with mission, being unflinchingly transparent, leveraging partnerships, iterating based on impact data, and nurturing a loyal community – other organizations can replicate aspects of Kiva’s remarkable impact in their own domains.

Kiva’s journey wasn’t without missteps or learning curves, but its willingness to learn and uphold its core values allowed it to not only achieve scale but also genuine social change, one loan (and one lesson) at a time.